But that shouldn’t divert attention from the huge impact he made on motorsport over the decades. Mosley helped Bernie Ecclestone to build Formula 1 into the commercial giant that we know today, and as FIA president he reformed and modernised the organisation and relentlessly pursued safety improvements throughout the sport. He also pushed to improve road safety, a campaign that has saved countless lives worldwide.

Combining fierce intelligence with a ruthless determination and an easy charm that could win over opponents, Mosley was a powerful personality who would surely have succeeded in any career that he chose to pursue. His major regret was that he was never able to enter mainstream politics, a legacy of his family background. He could never escape the fact that his father was Sir Oswald Mosley, the notorious leader of the British Union of Fascists. When the former Conservative and Labour MP married society girl Diana Mitford in Germany in 1936, Adolf Hitler was the guest of honour.

The Mosleys were interned in 1940, and Max – who was born in April that year – spent his early life with his parents in Holloway prison. After hostilities ended he had a peripatetic childhood, moving around Europe, including a spell in Germany, before going to Oxford University to study physics. He met and married wife Jean while still an undergraduate.

In 1961, Mosley discovered motor racing by chance after Jean was given tickets to the International Trophy at Silverstone. He was hooked at first sight, and a brief trial at a racing school further convinced him. But he was lacking funds, and he focused instead on studying law, while spending his spare time on exercises with the territorial army.

He was called to the bar in June 1964, gaining experience in court in cases such as motoring offences, before concentrating on patents. He subsequently earned some spare cash teaching law in the evenings.

Max Mosley, Brabham BT23C-Cosworth

Photo by: Motorsport Images

It took Mosley until 1966 to find the funding with which to kick-start his racing career and, after buying a Mallock U2, he entered his first Clubmans race at Snetterton. At first he was out of his depth, but by the following year he was winning races and setting lap records.

In June 1967 he managed to enter the Mallock in an international Formula 2 race at Crystal Palace, and therefore found himself on the same grid as drivers of the calibre of Bruce McLaren. Not surprisingly, he qualified and finished last in his heat. Enthused by the experience, Mosley decided to make the step up to F2 full-time for 1968, buying a Brabham BT23C from wheeler-dealer Frank Williams and entering it under the London Racing Team banner alongside friend Chris Lambert.

His first outing was at Hockenheim in April – the race at which Jim Clark lost his life – and he finished the two-part event in ninth overall. Further races followed, with little reward. By the time of the second Hockenheim race in June, his car was running under the Frank Williams banner, as teammate to Piers Courage. A huge crash after contact with Jo Schlesser gave him a fright.

“Afterwards we were sitting having a glass of wine in the evening,” he would recall. “And Piers said to me, ‘I don’t know why you do this, because it is dangerous. You’ve got a very good career at the bar, but I would only ever have been a very second-rate accountant.’ He was more or less saying I was quite mad to do it.”

Mosley’s main concern was for his wife, and Schlesser’s death in the French GP just a few weeks later was a further reminder of the dangers. He subsequently finished a respectable eighth at Monza, and then crashed at Zandvoort, where an earlier accident claimed the life of former teammate Lambert.

Bernie Ecclestone, Brabham team owner with Max Mosley, March Engineering team manager

Photo by: Motorsport Images

For the 1969 season, Mosley acquired a Lotus 59 F2 car. He campaigned it first at a Jarama event that was billed as a non-championship F1 race, but which attracted no serious entries. On his second outing at the Nurburgring he had a heavy practice crash after the suspension broke. Another failure in testing at Snetterton was the final straw and he retired from driving.

Mosley focused instead on a new project that would lead him to also abandon his law career. In 1968 he had met up with Robin Herd, an acquaintance from his Oxford days. Herd had left the aerospace industry to become McLaren’s first designer, and was now freelancing for Frank Williams. The two men gelled, and they soon hatched plans to enter Formula 1, and also build F2 and F3 cars. Herd brought Alan Rees and Graham Coaker on board, and March Engineering was born.

Mosley’s role was to find sponsors for March’s works F1 team, sell cars to customers, and generally promote the new organisation. The first F3 car was raced in late 1969 by Ronnie Peterson and James Hunt, but it was just a taster for a hugely ambitious programme for the following year.

Against the odds, Mosley convinced Ken Tyrrell, who needed to replace his Matra chassis, to buy Marches for world champion Jackie Stewart and Francois Cevert. At the first race of 1970 in South Africa, the Tyrrell entries were joined on the grid by STP-backed 701s for Chris Amon, Mario Andretti and Jo Siffert.

Stewart finished third and won the next two events, the Race of Champions and the Spanish GP. Amon then triumphed at the International Trophy with the works car. March had arrived with a bang and, while Tyrrell soon switched to its own chassis, the brash new operation had established itself as both a works team and supplier of customer cars.

In 1971, Peterson finished second in the world championship, despite not winning a race, and he also became March’s first European F2 champion. That year the team gave Niki Lauda his F1 debut – Mosley, who also engineered cars on race weekends, became close to both men. The team’s fortunes took a dive in 1972 when Herd’s 721X proved unsuccessful. Meanwhile, the customer side of the business thrived, with Frank Williams competing in F1, and huge sales in F2 and F3.

FIA President Max Mosley talks with Flavio Briatore

Photo by: Sutton Images

After a couple of low-key seasons for the F1 team in 1973-74, the colourful Vittorio Brambilla showed good pace in 1975, scoring the works team’s first grand prix win in the rain in Austria. The 1976 season was the team’s most hectic, as it fielded works cars for Peterson, Brambilla, Hans Stuck and Arturo Merzario, all with different sponsorship packages. Rejuvenated after losing his way at Lotus, returnee Peterson was a regular frontrunner, winning at Monza.

Funds were always lacking, and at the end of a dismal 1977 season with paying drivers the F1 team’s assets were sold to ATS, and the focus switched fully to F2 and F3. Mosley was no longer involved with selling customer cars and, with no requirement to find F1 sponsors, he left the company.

By then much of his attention had been diverted elsewhere. From 1970 he had taken a keen interest in the operation of what was then known as F1CA, the Formula 1 Constructors’ Association, whose main role was to negotiate finances with circuits.

Other team bosses were too busy running their own operations to devote much time to the bigger picture. Then, in 1971, Bernie Ecclestone became the owner of Brabham. Mosley knew him vaguely as the former manager and friend of the late Jochen Rindt. In F1CA meetings they recognised each other as kindred spirits, and their fellow bosses were happy to let them take charge. So began a friendship that would endure for 50 years.

They were a perfect team, Ecclestone’s streetwise negotiating savvy gelling with Mosley’s easy-going charm, sharp legal brain and long-term strategic vision.

This was the time of the blue-blazer brigade, with organising clubs run by an old-boy network, and no consistency between events. The Mosley/Ecclestone combination proved formidable, and over the years they built up the influence of the teams, getting better deals from race promoters worldwide, and swinging the balance of power away from the CSI, the sporting arm of the FIA.

It was not an overnight process, and it continued through the 1970s. Then, in 1978, French federation boss Jean-Marie Balestre became president of the CSI, soon changing its name to FISA. Balestre made it clear that he wanted to control F1, including the commercial side that the recently renamed FOCA had built up. From the start there was confrontation.

Bernie Ecclestone, Brabham team owner with Max Mosley, March Engineering team manager

Photo by: Motorsport Images

At the end of 1980, FOCA announced plans for its own championship, with the backing of many event promoters. In early 1981, as a show of strength, the organisation held a non-championship race in South Africa.

Shortly afterwards the first Concorde Agreement, which formally handed the commercial control of the sport to Ecclestone and FOCA, was signed – and Mosley was one of its main architects. Initially it was to run for only four years, but it would be successively renewed.

Mosley left his FOCA activities at the end of 1982, and for a while focused his efforts on politics, hoping to become a Conservative MP. His obvious concern was that his father’s legacy would be an issue, even after his death in 1980. He worked for the party at the 1983 general election but, when his attempts to get on the candidates’ list met with little enthusiasm, he reluctantly gave up his ambitions.

He turned his attention back to motorsport. With Ecclestone’s and Balestre’s support, in 1986 he became president of the FIA’s manufacturers’ commission, representing the car makers’ involvement in non-F1 activities, notably rallying and sportscar racing. He also set up a design business with Nick Wirth.

The commission job gave Mosley a seat on the World Motor Sport Council and an opportunity to network and successfully establish himself as an FIA insider.

In 1991, Balestre’s latest term as FISA president expired, and Mosley stood against him. Against the veteran Frenchman’s expectations, Mosley won by 43 votes to 29. Two years later he replaced Balestre as president of the full FIA, and he set about modernising and restructuring the outdated organisation.

In 1994, the F1 world was rocked by the deaths of Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger at Imola, and a series of other serious accidents. Action had to be taken, and in what was his finest hour Mosley reacted fast and decisively in attempting to slow the cars and address safety issues. Looking to the future, he set up a safety committee, chaired by Professor Sid Watkins and including Charlie Whiting, Harvey Postlethwaite and Gerhard Berger.

Nick Wirth, Simtek Team Principal talks with Max Mosley, FIA President about tragic death of Roland Ratzenberger

Photo by: Sutton Images

Its initial mandate was to conduct research into cockpit safety, corners and runoffs, and barriers. It was the start of a formal and concerted effort by the FIA that quickly made significant progress, and which continues to this day.

Mosley was re-elected as president in 1997, 2001 and 2005. The safety campaign aside, his tenure included many significant episodes in F1 history, notably the spy scandal of 2007, when McLaren was accused of benefiting from information stolen from Ferrari, and the threat from the manufacturers of a breakaway championship, which he and Ecclestone successfully saw off.

Mosley was ahead of the game in many areas, pursuing a carbon-neutrality policy as early as 1995, and later backing KERS and a return to small turbo engines as ways of promoting a more energy-efficient sport. He also tried hard to reduce costs in F1, exasperated by the money wasted by the teams.

In March 2008, Mosley’s world was turned upside down when the News of the World published a story about an encounter with five prostitutes, complete with video footage. His life was never to be the same again. He survived a storm within the sport, winning a vote of confidence from the FIA. But he had been irreparably damaged, and eventually he announced that he would not stand again for the presidency in 2009.

Having won a legal action against the News of the World‘s owners, he became a tireless campaigner for privacy rights and press reform. In 2015 he published an autobiography, detailing his career with March, FOCA and the FIA, as well as his legal actions and the privacy campaign. More recently he contributed to a film documentary that covered similar ground, and which will be released in July.

Mosley will forever remain a controversial and divisive character, and he created a few enemies over the years. Love or him or loathe him, there are racing drivers and thousands of people from many other walks of life who are alive today as a direct result of his efforts. He remained chairman of Global NCAP until as recently as 2017.

A decade earlier, when this writer asked him what he would like his legacy to be, his answer was unequivocal. “The thing about F1 is that you can make a huge effort there and you maybe save one life every five years,” he said, “whereas on the roads it’s literally thousands of people.

“If I’m still alive when I’m 80, I’d like to be able to sit down and think I really made a difference, and there are a lot of people walking around hale and hearty who would not have been if I hadn’t made the effort. If I can say that to myself, I’d be very pleased.”

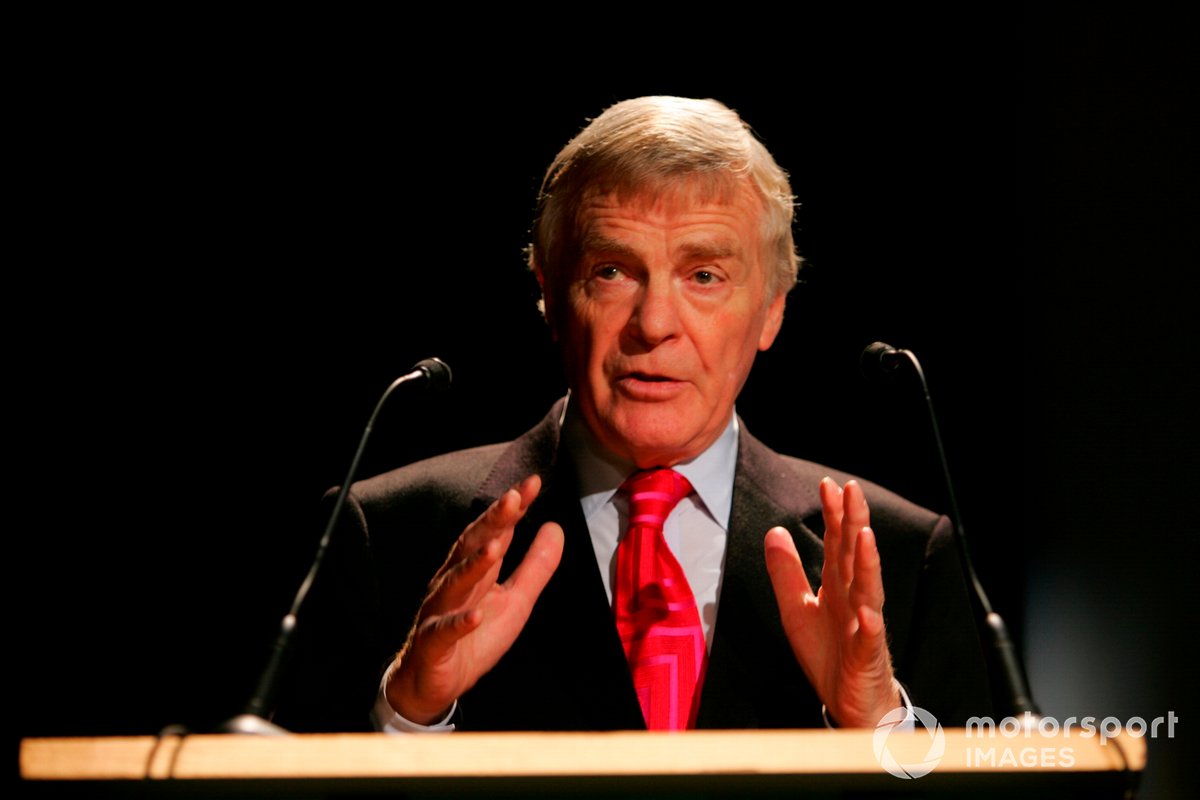

Max Mosley, FIA President

Photo by: Sutton Images

shares

comments