In 2021 Formula 1 teams are operating for the first time with a success handicap created by a sliding scale of aerodynamic testing limits based on last year’s results.

It means that Williams, as the worst performing team of 2020, can now do more aero R&D work in the windtunnel and on CFD than everyone else.

Correspondingly world champions Mercedes can do less than the other nine teams.

In its first season of operation the slope of this sliding scale is relatively gentle, but from 2022 it becomes much steeper, and its potential impact will be greater – but it may well achieve the main aim of closing up the pack.

The principle of penalising the top players, or helping those in need, is a new one in F1 but it is familiar in MotoGP, where struggling manufacturers get extra testing and engine updates and so on.

Over the years various ideas have been kicked around by the FIA and the F1 teams, such as success ballast and reverse grids.

It was generally agreed that most were too artificial, and the focus switched from a direct impact on races to the heart of what makes the top teams so successful – their R&D capabilities.

The concept of giving those further down the field a chance to catch up by being allowed to conduct more aero work emerged.

“I’m pleased with it, because I think it’s a gentle correction,” F1 boss Ross Brawn said last year.

“It still maintains the meritocracy, you’ve still got to go out on the track and win the race.

“We’re not doing anything to handicap the driver when he’s out on the track – it’s not success ballast.

“It’s rather like the NFL with the draft, where the least successful teams get the greatest opportunity initially, but they still have to deliver. It’s not like they have points given to them.

“I think it will have a gentle effect on correcting the competitiveness of the field, without distorting it.”

Those further down the grid – and desperate to catch up – welcomed the idea.

“It’s an interesting exploration of a handicap system for F1,” said then Renault boss Cyril Abiteboul.

“But one which is in my opinion is much more relevant with F1 DNA than ballast or balance of performance based on the competitiveness of the car.

“It’s happening at the factories, and anyway the factories are not equal on the basis of their investment, their people, and so on.

“It’s a very small distortion to the equality of teams that are anyway not there.

“In my opinion it’s a very acceptable first try of a handicap system that should make the grid more competitive, which again is great for the sport.”

As Brawn suggested, it’s still a meritocracy, with successful work by clever people rewarded.

“The ATR restrictions will reward those who have an efficient tunnel programme,” said Aston Martin team principal Otmar Szafnauer.

“If you can run things efficiently and don’t have to do experiments twice, and you can get good repeatability out of your tunnel, all that matters.

“And therefore you get more performance as opposed to trying to recalibrate all the time. You run a good quality, efficient tunnel programme, you’ll benefit.”

What are the new F1 aerodynamic testing limits?

So how will it work? The first thing to know is that Aerodynamic Testing Restrictions [ATR] have been in the F1 Sporting Regulations for years, under Appendix 8.

What can and can’t be done is covered in great detail, and over time any loopholes, such as information being shared across teams, have been addressed and closed. The policing system has been honed, and it works.

The season is divided into six Aerodynamic Testing Periods [ATPs] of nine, eight, eight, ten (including the August summer shutdown), eight and nine weeks.

Each ATP period incorporates a limit of how much aero work can be conducted, and teams have to report to the FIA exactly what they’ve done at the end of each period. Thus the limits are monitored “live” during the season, rather than at the end of it.

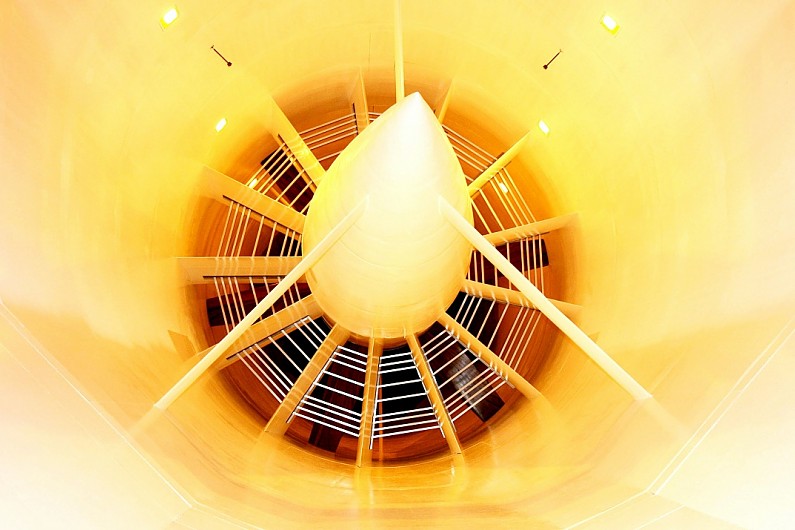

Windtunnel testing is subject to three key parameters. In 2020 the limit for each ATP period was 320 runs, 80 hours of “wind on time”, and 400 hours of “occupancy,” a number that includes the downtime between the actual runs on each tunnel shift.

To give some context 400 hours of occupancy represents 50 eight-hour shifts in a typical eight week, or 56-day, period.

CFD usage is subject to a separate and extremely complex set of restrictions that require teams to submit full details of the systems and computing power at their disposal.

All of this is well proven and understood by everyone. The only difference for 2021 is that the limits are different for each team, based on the 2020 world championship order, and using the established 2020 ATR figures as a starting point for the fifth-placed team. This is how it pans out:

2021 ATR Testing Limits (1 January-30 June)

1. Mercedes: 90%

2. Red Bull: 92.5%

3. McLaren: 95%

4. Aston Martin: 97.5%

5. Alpine: 100%

6. Ferrari: 102.5%

7. AlphaTauri: 105%

8. Alfa Romeo: 107.5%

9. Haas: 110%

10. Williams: 112.5%

One important detail is that there is a re-set on 30 June, which equates to the end of the third of the six ATP periods.

At that stage the above table will be changed to reflect the 2021 world championship order. Based on the current calendar that will be after round eight, the French GP.

How much impact will the new F1 aerodynamic testing limits have?

Will the 2.5% delta between 2020 champions Mercedes and runners-up Red Bull create a significant advantage for the latter?

Over the three ATPs to the 30 June re-set it adds up to a difference of six “wind on” hours, or 24 tunnel runs, in the first half of the season.

That’s a useful gain for Red Bull, but not necessarily one that will make a tangible difference. It’s the same for the other 2.5% gaps between teams adjacent to each other in the 2020 championship table.

Where it gets more interesting is when you look at gaps of two, three or more places between teams. And the most intriguing aspect of that concerns Ferrari, a lowly sixth in last year’s standings.

Here’s how Ferrari’s aero testing limit compares with the five teams it is chasing for the first half of 2021.

Windtunnel Limit for top six teams (1 January-30 June)

Mercedes: 864 runs/216 wind on hours

Red Bull: 888 runs/222 wind on hours

McLaren: 912 runs/228 wind on hours

Aston Martin: 936 runs/234 wind on hours

Alpine: 960 runs/240 wind on hours

Ferrari: 984 runs/246 wind on hours

That delta between Ferrari and Mercedes of 120 runs and 30 hours for the six-month period before the 30 June re-set is not insignificant, and if used effectively, it could be of immense value.

After that re-set, assuming that Ferrari is higher than sixth in the championship, the Maranello team will have less of an advantage over its main rivals over the remaining six months of 2021.

Why are F1’s new aerodynamic testing limits such a challenge?

The key challenge is that in 2021 windtunnel and CFD work has to be shared between developing the current car and preparing for the huge rule changes for 2022 and a very different package.

Every team will have to decide how to allocate its scarce windtunnel and CFD resources across the two projects, and thus every run or hour in the tunnel is correspondingly even more precious this year than in 2020.

The teams facing the tightest restrictions face a particularly tough challenge, as they have to really focus.

“We were lucky enough to be good last year,” Mercedes technical director James Allison noted last week.

“And unfortunately, we pay the price for that a little bit in 2021 and beyond because we get to use less of that fundamental asset, the windtunnel and the CFD.

“For us the challenge has been, how do we react to this new regulation in the most positive way? How can we make sure that we don’t get tripped up by it?

“And there the challenge has been, well if we are not allowed to use as much of our windtunnel and our CFD as we were previously, how could we adapt our world so that we get more and more out of every single opportunity in that windtunnel.

“We’ve only got one run in the windtunnel, let’s make that run as valuable to us as possible.

“If we are only allowed to do a small amount of CFD calculation, let’s make it so that the methodology and approach to those CFD calculations are as valuable as possible.

“So, we’ve tried to adapt our approach to this, so we mitigate and maybe even completely offset the effect of this reduction in the amount that we are allowed to use these fundamental tools.”

When will F1 teams switch resources to their 2022 cars?

All teams worked solely on their 2021 packages at the end of last year, as they were forbidden to start on 2022 aero testing until 1 January.

Obviously they couldn’t make a complete switch on that date, however tempting it might be. They still have a lot of work to do to optimise the 2021 cars both prior to the season and as it progresses.

Nevertheless at some point this year every team will gradually ease off on current development until their aero focus is entirely on the new rules.

The timing of that switch is always a big talking point, especially during any season that precedes major rule changes. It will be even more relevant this year, for various reasons.

Don’t forget that while teams are using their 2020 cars as a starting point for 2021, and much is carried over, aero development has remained free. Thanks to the freeze on mechanical parts it is by definition the key area where a competitive advantage can be found this year, along with the power unit.

In addition for there’s a package of four aero rule mods, intended to trim downforce and take load off Pirelli’s tyres. Together these add up to a significant change to the airflow over and around the car, and lessons will be learned and gains found well into this season.

The world championship battle is always a key factor in the decision to switch towards the following year’s car. Traditionally teams fighting for the title, or in a close contest for lucrative positions further down, are wary about stopping development on their current car too early, thus potentially losing out to rivals who kept pushing on.

Each position in the final world constructors’ table represents not just prestige, but also a significant amount of cash from the F1 prize fund. The ATR sliding scale has added a further dimension to the championship position equation, especially as it will have an even bigger impact from 2022.

The numbers outlined earlier apply only to 2021, because from next year a steeper sliding scale is introduced as follows.

2022-25 ATR Testing Limits based on previous year’s championship

1st place: 70%

2nd place: 75%

3rd place: 80%

4th place: 85%

5th place: 90%

6th place: 95%

7th place: 100%

8th place: 105%

9th place: 110%

10th place: 115%

The deltas between teams will be bigger and the success penalty correspondingly more significant. For example, the gap between first and sixth place doubles from 120 runs to 240 for the first six months of the year.

It means that a team that gets a flying start under the new rules in 2022 and wins the title will find it much harder than usual to maintain that momentum into 2023 and beyond, if others make good use of their extra resources.

The most talented aerodynamicists, with the most effective CFD programmes and best calibrated tunnels, will always have an advantage. Quality over quantity plays a role, in other words.

However, the delta in quantity between teams will become so significant that it is sure to have some impact, and we could witness a see-sawing of form between seasons – which is exactly what F1 and the FIA want.

No doubt a debate over the rights and wrongs of the system will ramp up as its impact becomes more apparent over the next couple of seasons.

“It was amusing really,” Brawn said. “One of the Mercedes people was complaining to me about it, and I said, ‘You’re assuming that you’re always going to win. Just think for a moment, you’re second or third, wouldn’t you like a bit of assistance?’

“And it suddenly dawned on him that if they didn’t win, this would be quite useful.”