Much-maligned given his record for the most races without a point and his disastrous two-race foray with Ferrari in 2009, Luca Badoer is perhaps the embodiment of the old adage that your most important race is your last one. JAMES NEWBOLD argues that his reputation is undeserved

It will have been small consolation to George Russell, after his superb drive for Mercedes in the 2020 Sakhir Grand Prix was rewarded with only a ninth-place finish, that at least 2021 holds no chance of him claiming an unwanted Formula 1 record.

If his team’s pitstop faux pas in fitting tyres intended for Valtteri Bottas had been met with a disqualification, and this year’s Williams proves no improvement on the past two seasons, then there was a real chance that round 13 at Spa might have featured Russell starting the most grands prix without scoring a point, to surpass incumbent Luca Badoer.

PLUS: The F1 sanity that left Russell with some Sakhir solace

The 1992 International Formula 3000 champion was a much better driver than his unfortunate three-letter prefix would suggest and, while perhaps not world champion material, certainly doesn’t deserve the reputation for ineptitude that was cultivated by his disastrous two-race comeback as a substitute for Felipe Massa in 2009.

That Badoer has the pointless record at all owes much to the changing nature of the points structure used in F1. In his debut season with the woefully uncompetitive Scuderia Italia Lola in 1993, he was seventh in an attritional San Marino Grand Prix (one lap behind JJ Lehto, whose Sauber expired two laps from the finish), but points were only scored down to sixth place back then.

He registered another 10 top 10 finishes in his 50-race F1 career, which would have easily been enough under today’s points system for next closest Charles Pic (39 starts for Marussia and Caterham) to have the dubious record instead.

Badoer’s career is perhaps defined by a lack of momentum following his breakthrough 1992 season, capitalising on his Crypton team being the first outfit to adopt monoshock suspension to win four times and beat a field that included Rubens Barrichello and David Coulthard (winning by a remarkable 21 seconds in a crushing display at Enna).

It also meant he was one of only four drivers (the others being Stefano Modena in 1987, Christian Fittipaldi in 1991 and Jorg Muller in 1996) to win the F3000 title at the first attempt.

“I’m not in competition with Michael or Rubens. But, of course, I have a special opportunity to see that my times are similar to theirs, which means that I’m a fast driver too” Luca Badoer in 2004

The 1993 Lola he was saddled with had been produced in double quick-time and never saw a windtunnel until after the drawings were already complete. Hardly the sort of machine for a rookie to build confidence, veteran team-mate Michele Alboreto was Badoer’s only barometer but he beat 1985’s F1 runner-up 8-6 in qualifying before the team elected not to enter the final two flyaway races.

PLUS: How to build a slow Formula 1 car

“I had two options at the time,” Badoer recalled in a 2004 interview with Autosport. “I could join Tyrrell, which was a good career move, or Scuderia Italia. I got it wrong.

“On paper it looked good. They had Lola chassis and Ferrari engines. Unfortunately, the T93/00 was a bad car.”

Scuderia Italia merged with Minardi in 1994 and Badoer was demoted to test driver, but returned once Alboreto retired for 1995 alongside team favourite Pierluigi Martini. Minardi easily had the measure of strugglers Pacific and Forti, but that wasn’t saying much.

Still, it was better than the Forti Badoer was lumbered with in 1996 – giving Badoer an acute case of deja vu as he and former F3000 sparring partner Andrea Montermini once again struggled to qualify. Fittingly, the team didn’t see out the year and, while Badoer’s stock took another dip, Coulthard was in the process of establishing himself at McLaren while Barrichello was building a burgeoning reputation at Jordan.

It’s perhaps unsurprising therefore that Badoer had few chances to score points in F1. That much didn’t change in 1999 on his return to Minardi – the team waiting until late February to sign the best driver still available when its hopes of signing a funded second driver to partner Marc Gene didn’t materialise – but when he did at the European Grand Prix, they were taken away by a problem outside his control.

One of the most enduring images of that crazy day is of Badoer, weeping by the side of his expired M01 having risen to fourth amid the chaos, only for a gearbox failure to strike with 13 laps to go. Adding insult to injury, team-mate Gene – who Badoer outqualified 10-5 in their races together – inherited the final point for sixth place.

That Badoer was in the Minardi for that race at all was a point of consternation for, having been appointed as Ferrari’s test driver in 1997, he might well have expected to have the call-up to race for the Scuderia in the absence of team leader Michael Schumacher, who had broken his leg at Silverstone.

Instead, the seat went to Mika Salo, who had lost his place at Arrows to the well-backed Tora Takagi shortly before the Australia season-opener, and who had already driven three grands prix that year subbing for an injured Ricardo Zonta at BAR. Salo memorably gave up victory at Hockenheim for title-challenging team-mate Eddie Irvine and took a third place at Monza after Mika Hakkinen crashed out, but otherwise struggled for form in his five races with Ferrari. Only 18th on the grid at the Hungaroring – ironically just ahead of Badoer – was the nadir as Salo finished a twice lapped 12th, and he was nowhere at the Nurburgring on Badoer’s day of days.

Whether Badoer would have been an improvement on the Finn is difficult to determine, but he had knowledge of the team’s operations and how the car worked that would certainly have short-cutted his learning curve. But, as Stoffel Vandoorne discovered in 2020, the plug-and-play option isn’t always the one that gets the nod…

A decade of testing for Ferrari followed, with Badoer playing a hidden if important role in Maranello’s steamroller of titles between 2000 and 2004 completing between 20,000 and 25,000 miles per year to develop cars for Schumacher and Barrichello.

“Sometimes when you test, you have to think about what’s good for the team rather than how quick you are,” Badoer explained in 2004. “I’m not in competition with Michael or Rubens. But, of course, I have a special opportunity to see that my times are similar to theirs, which means that I’m a fast driver, too.

“As a test driver, you have to be fast anyway, otherwise you don’t experience what they do in the car. If you are one second slower than your team-mate, you can’t have the same feeling for the car, and you can’t reproduce the same problems that he might have with it.”

Badoer turned down several offers to return to racing in preference to continue testing with Ferrari, explaining in 2004 that “after seven years it’s still very emotional every time I step into the car“.

Finally in 2009, Badoer got his long-held wish of racing for Ferrari when Schumacher – the Scuderia’s initial preference to replace Massa after the Brazilian was struck on the helmet by a spring from Barrichello’s Brawn in Hungary – decided his neck needed longer to heal following a motorcycle crash.

The introduction of KERS in 2009 meant Badoer’s bank of knowledge was less relevant than at any time in the previous decade

There can be no denying that Badoer’s lack of performance at Valencia and Spa – both times qualifying slowest – was galling for a Ferrari driver. “Graduated from slot-like to snail like and qualified 1.5s off the next driver,” was Autosport’s withering take on his Valencia performance, which earned a 0.5 out of 10 score in the driver ratings. Spa wasn’t much better, scoring a 1 for finishing 14th as team-mate Kimi Raikkonen took victory.

But what can be added is context. It was Badoer’s misfortune that the new-for-2009 aerodynamic regulations, combined with a freeze in engine development, conspired to create the closest season in F1 history between the front and the back of the field, with a Supertimes average of 1.241% between the fastest (Red Bull) and the slowest (Force India, which took pole at Spa thanks to Giancarlo Fisichella).

PLUS: When was Formula 1 closest?

That meant Badoer’s ring rustiness was brutally exposed in a manner it may not have been the year previously, when Ferrari was a far more competitive prospect. In fact, 2009 was Ferrari’s least competitive season since 2005 (also fifth-fastest), having had the fastest car on average in 2006 and 2008 and second-fastest in 2007.

The struggles of Badoer’s replacement, Fisichella, in the final races of 2009 attest to the fact that the F60 wasn’t an easy beast to tame, with the three-time grand prix winner managing a best qualifying position of 14th and equalling Badoer by qualifying last for the inaugural Abu Dhabi Grand Prix.

PLUS: The spectacular peaks and troughs of Ferrari’s cyclical history

It was also the season that testing was dramatically cut, while the introduction of KERS also meant Badoer’s bank of knowledge was less relevant than at any time in the previous decade.

All this is largely forgotten whenever Badoer’s name is mentioned. He has become something of a comedy figure, which is highly undeserved when the balance of his career is scrutinised.

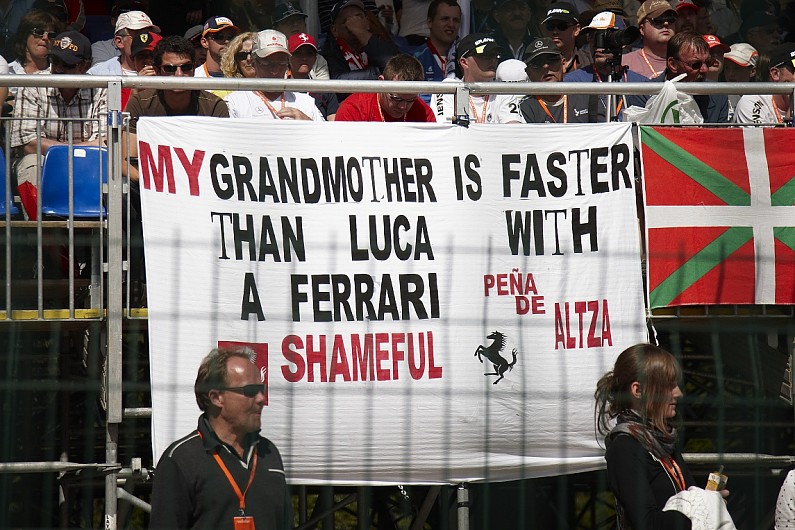

But, as is so often the case, it’s the final chapter for which he is remembered, and the scathing trackside banner at the 2009 Belgian Grand Prix – “My grandmother is faster than Luca with a Ferrari. Shameful” – that proved an epitaph for his career.