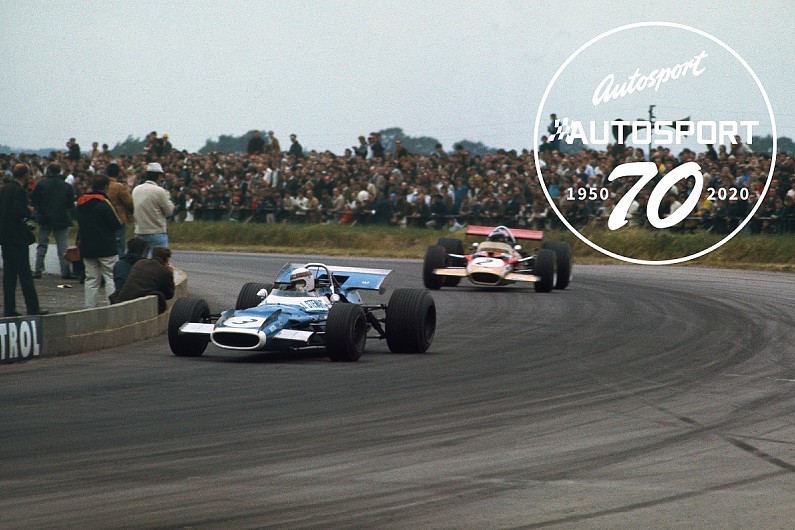

While Formula 1 drivers and team bosses dominate the limelight, team mechanics remain the unsung heroes hidden in plain sight. But, in an article originally published in Autosport magazine on 13 November 1969, attention turned to a pair of New Zealanders key in helping Jackie Stewart to his first world title

The best racing driver in the world is only as successful as the preparation of his car permits. Poorly prepared cars don’t win races, so it follows that the mechanics who work on a world champion’s racing car must be fairly special people. They are. Jackie Stewart won the world championship for the Tyrrell team this year after a string of wins that could only have come from a clinically-efficient team. Tyrrell set out with a master plan for grand prix racing that called for Stewart, a three-litre Ford-Cosworth engine and the Matra chassis. Added to that he had to have a top team of mechanics. There were six of them in the Tyrrell pits this season and they worked as a team, but any team needs a leader and, since he takes the blame if things go wrong, it follows that he takes the credit when things are going well.

New Zealander Max Rutherford, 27, was chief mechanic in overall charge of the two-car Tyrrell team, responsible for preparation of the Matras and for the general administration of the day-to-day details under the ever-present eye of team boss Tyrrell. Next man on the ladder was another New Zealander, Roger Hill, who was more or less Stewart’s personal mechanic and always worked on Jackie’s car.

Rutherford and Hill both came from New Plymouth in New Zealand and both arrived in England at the start of 1965 to work as mechanics for four of their friends who planned to race motorcycles in England. Rutherford’s career as a motorcycle mechanic lasted barely longer than it took his ship to dock. He had a letter of introduction to Roy Billington – yet another New Zealander – who was chief racing mechanic at the Brabham factory, so he trekked down into the wilds of Surrey. Billington wasn’t sure what he could do to help his new arrival, but Ron Tauranac arrived along in the middle of the conversation, was introduced, and offered Rutherford a job.

“Ron asked me what I was doing and I told him I’d like to work on racing cars if I could get a job somewhere,” says Rutherford. “He said I could start immediately if I had my overalls with me, so I rushed off and bought a pair, found myself somewhere to live, and started at 8:30am the next morning. I was still there at 8:30am the following morning! We were working to get Graham Hill’s Formula 2 car ready for a race at Oulton Park, and my first day at Brabhams had lasted 24 hours… I thought if this is racing, I’m not very keen on it. But I stuck it out.”

Like many of the New Zealand mechanics in European racing, Rutherford has his ambitions to follow in the footsteps of Bruce McLaren, Denny Hulme and Chris Amon, and be a racing driver. In Max’s case, motorsport ran in his family. His father is a carpenter in New Plymouth and is now an area steward for the national body controlling racing in New Zealand. At one stage a few years ago, Max’s father was secretary of the local car club, his eldest brother Don was president of the local speedway club, and Max was secretary of the local go-kart club.

Karting was where it all starts for Max. He took a technical course at school and left to serve an apprenticeship with the local Ford agents. In his spare time, he built himself a go-kart and raced it with some success, leading on the last lap of the finals in his class championship when the engine blew. A kart crash put him in hospital with a broken leg and, while he was hobbling round in a plaster cast, a local firm – St Albans Motors – offered him a drive in a three-quarter midget speedway car if he would rebuild it from its rather sorry shunted state.

As Brabham had done years before, Rutherford learnt the ungentle art of sideways motoring in cinders, winning the provincial championships after a season of learning in a little front-engined 500cc JAP special, and finishing third in the New Zealand championships. For the next season, he built a car of his own design with a 500cc BSA engine tuned for alcohol mounted in the rear and independent suspension all round, which was a fairly advanced specification for a speedway midget. One of Rutherford’s intentions with the new car was to get off the cinders and into some more refined competition, and he ran it in a local hillclimb, clipping the record by three seconds in practice and going inside that time on his official run, being beaten by half a second by Jimmy Boyd who was to win the national hillclimb championship that year in his Lycoming special. A few months later, Rutherford sold the midget on the strength of its performance in the hillclimb, and got enough cash together to pay his fare to England.

“My first day at Brabham had lasted 24 hours… I thought if this is racing, I’m not very keen on it. But I stuck it out” Max Rutherford

“Four friends were coming to England to race motorcycles, and they offered Roger and me jobs as mechanics if we wanted to come,” Rutherford recalls. “I was young and silly and I had the money for the fare, so I went with them. I had an idea that I might be able to have a go at racing when I got to England, maybe in a Lotus Seven or something like that, but when I arrived I had hardly any money left.”

The job with Brabham solved the financial crisis, but there wasn’t much glamour or excitement down in the New Haw factory, so when American driver Cliff Haworth bought a new Formula 3 Brabham and needed a mechanic, Rutherford went along, although he knew he wasn’t going to be paid. “I thought at the time that this could be a good chance to get into racing even if I wasn’t getting paid – like a mug – so I went along and did almost a full season on the continent,” says Rutherford.

Working without pay might not have seemed very smart at the time, but the experience gained in that first season was valuable, and he entertained offers of 10 different jobs at the end of that 1965 season. He signed up with Charlie Crichton-Stuart to look after the Stirling Moss Racing Team Formula 3 Brabham, and they started off well by winning the four-race Argentine Temporada series.

“I had a reasonable sort of name as a mechanic by this time but, by the end of the season, after 18 months of touring round, racing was starting to go a bit sour for me,” Rutherford says. “I was beginning to realise that it was a dead-end game and if I didn’t get out and go home to New Zealand, I’d never get out. I had met my Irish wife-to-be, Christine, about this time and I was working on one of Stirling Moss’s garages to earn some money to get married. I even worked for a couple of weeks in the Christmas holidays slinging mail bags around in the Post Office. I was all set to get married and give up the racing game.”

“I talked to Jack”

Then the telephone rang one evening. On the other end was Billington wondering if Rutherford would be interested in working on the Brabham Formula 1 team in 1967. “After two years in Formula 3, I wanted to get out, but I thought a year in Formula 1 wouldn’t hurt me, so I went down and talked to Jack,” he says. As it turned out, Rutherford looked after Brabham’s Formula 2 car the following season and, towards the end of what wasn’t a very successful year, he followed up rumours that Tyrrell was going to run a Formula 1 team in 1968, and asked Ken for a job.

He started working in the Tyrrell workshop to one side of the muddy yards in the grounds of the old brickworks, which also serves as a base for Tyrrell’s timber trucks, and he stayed with the team through 1968 and 1969. Stewart’s broken wrist probably cost the team the world title the first year but, like Samson, Stewart found new strength in long hair, and he swept through to his title win this year.

PLUS: The 10 greatest races from Britain’s best F1 driver

Racing mechanics don’t see the glamour side of the driver; they aren’t the people he’s usually waving at when he takes the chequered flag, although every driver has a very close working relationship with his team of mechanics. What is Stewart like to work with?

“Of all the drivers I’ve worked for, he’s the easiest,” says Rutherford, carefully working out the answers when the questions get political rather than biographical. “He doesn’t demand anything. The only time he gets a bit irritable is when he’s only second fastest and he can’t understand why. He’s trying his hardest but it isn’t good enough, so he starts looking for something else, but he’ll never say outright that he thinks it’s the fault of the mechanics. He’ll call the designer a few names at times when things are going wrong. He’s good to work for in that he doesn’t understand the very intricate workings of the car. He’s got a rough idea of how it all happens, but if something goes wrong, he’s just as happy to go back to his hotel and leave you to sort it all out, whereas Jack or someone like that would be hanging over your shoulder annoying hell out of you until you fixed it.”

Ken Tyrrell gives the impression that he wouldn’t have gone Formula 1 racing if he hadn’t carefully worked out the winning combination in the first place. What is so special about the Tyrrell approach to racing?

“He looks into every little detail that he can possibly look into,” says Rutherford. “In another team, if a mechanic finds something wrong, he’s just as likely to fix it himself and not tell anyone because he doesn’t think anyone is interested, but the policy in the Tyrrell team is always to let it be known what you’re doing. If you don’t, you’ll soon get caught out, because like it or not Ken is looking over your shoulder and he sees what you’re doing anyway. He’s just as anxious as you to get to the bottom of any problem, and if we can’t find the answer ourselves he doesn’t hesitate to bring in the big companies who make the components we’re having problems with. I’m certain that this is why the team has been so successful, because Ken is always so interested in what’s going on.”

There are six regular mechanics – the New Zealanders Rutherford and Hill, Englishmen Keith Boshier, Alan Clegg and Eric Sykes, Peter Hass who is German, and Frenchman Marcel Vieuble, who is mechanic to Beltoise when Jean-Pierre is driving the second Formula 1 Matra.

“It’s certainly a good life for a couple of years but, after that, you’re only too pleased to get out. For a single man it’s ideal for a couple of years, but after that he’s seen most of the world – or rather he’s seen parts of most of the world” Max Rutherford

Compared with the daily drudge of the average garage mechanic, a racing mechanic’s life is glamorous, but Rutherford doesn’t altogether agree.

“It’s certainly a good life for a couple of years but, after that, you’re only too pleased to get out,” he admits. “For a single man it’s ideal for a couple of years, but after that he’s seen most of the world – or rather he’s seen parts of most of the world. He only sees the hotel and the race circuit and the piece of road in between. He can say he’s been to America, but he can’t say he’s seen America. Everyone thinks its fabulous and we’re touring round seeing the world, but we only see parts of it really. I came here for 18 months’ working holiday and I’ve been here five years now, so I think it’s time I went back home. I think I’ve probably had two years too much. I’m getting grey hairs and I’m only 27, so it can’t be doing me any good. I’ve been offered a job working in New Zealand, but I don’t know – I’d like to try something entirely different – maybe go into a small manufacturing business.”

New Zealanders are head mechanics in the Lotus and Brabham teams as well as in the Tyrrell Matra team, so I asked Rutherford why he thought this was so. What did New Zealand mechanics have that others apparently didn’t?

“The only thing I can put it down to is that they’ve all come 12,000 miles from home and they’re living out of a suitcase anyway, so they don’t mind a bit more travelling around,” he suggests. “But there are other reasons. I think the New Zealand mechanics are adaptable to anything, whereas the average English mechanic is only good at being a mechanic, or good at being a panel beater, or a good welder, but he doesn’t have a little bit of everything. A mechanic in New Zealand has to do a bit of everything, and also most of the racing mechanics from home have had a bit of racing experience themselves, and this certainly helps.”

Trying the driving side

A frustrated racing driver doesn’t always make a contented mechanic, but Rutherford was fortunate in having the opportunity to work his ambitions out of his system. While he was working for Crichton-Stuart, Charlie was an instructor at Brands Hatch, and Rutherford often borrowed the Brabham for a few quiet laps when the track wasn’t busy.

“I did part of a course with Tony Lanfranchi in Lotus Cortinas and things, and then I borrowed the Brabham Formula 3 car complete with trailer and Cortina estate car and went up to Cadwell Park, where Crichton-Stuart had organised starts for me in a couple of formule libre races,” he says.

He ran on dry tyres in the rain and scored a fourth and a third, finishing second in the Formula 3 class both times, but if that was being a racing driver he didn’t want to know, and he was able to return Crichton-Stuart’s racing rig happy that he had satisfied his ambition.

European motor racing seems to be an irresistible attraction for racing enthusiasts from New Zealand and Australia, so I asked Rutherford if he had any hints on how aspiring racing mechanics went about getting jobs. He wasn’t very encouraging.

“Until the past couple of years, the idea was to do what I did and work for a manufacturer like Brabham or McLaren or Lotus and get a bit of experience working on modern racing cars before going out and looking after a Formula 3 car for someone, but it’s getting harder to get jobs at the factories now,” he says. “The teams don’t want people coming and going all the time. It’s a lot more difficult now. But, on the other hand, there are more people racing now, and there are more opportunities if you can convince a driver that you know something about looking after a car.”

In motor racing these days, who you know is almost as important as what you know, and inside information or introductions can often open closed doors. Rutherford was able to get his first job at the Brabham factory through a letter of introduction to Billington, and in his turn he was able to organise a job for Hill, first with Charles Lucas and then with the Tyrrell team, where Hill now has one of the top positions.

Racing mechanics don’t have it easy but, if they didn’t like the life, they wouldn’t do it. Their sort of work is like a drug and they’re hooked on it. They don’t have a trade union battling on their behalf for sane working hours. If they did, there wouldn’t be any racing. Imagine the drama there would be if racing mechanics decided to ban those too frequent all-nighters before a race: there would be a few blank spaces on the grid!

In general, the racing mechanics are an unsung bunch of hard workers who get little of the credit and less of the cash when their car wins, so they’d like us to remember that they’re people too. And if it weren’t for people like Rutherford, Hill, Boshier, Clegg, Hass and Sykes, Stewart and Tyrrell wouldn’t have a world championship title to tell their grandchildren about.