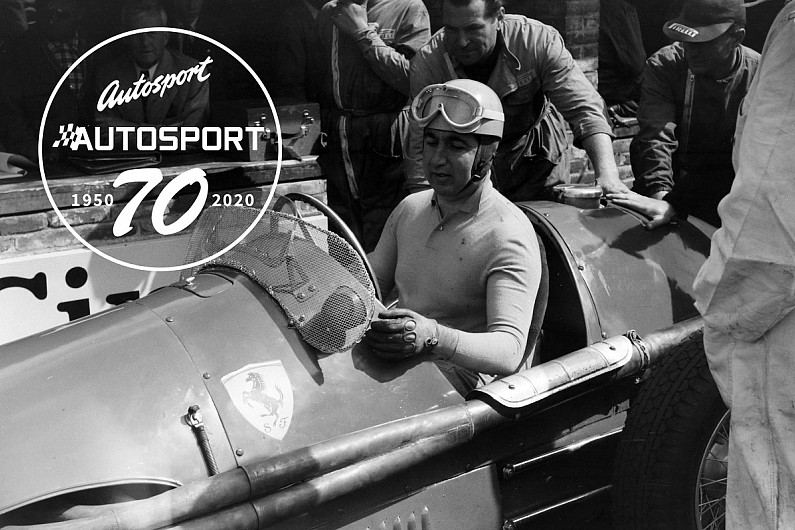

It’s 65 years since double world champion Alberto Ascari was killed in an unexplained testing accident. NIGEL ROEBUCK told his story, in a feature first published in Autosport magazine on 2 December 1976

Mario Andretti once said that he figured he had been put on this earth to drive race cars, and the same was true of his childhood hero.

Alberto Ascari came from a motor racing family. Antonio, his father (below), was one of the very greatest drivers of the 1920s, the flamboyant star of the Alfa Romeo team run by Scuderia Ferrari. But when Alberto was seven years old, in 1925 his father was killed in the French Grand Prix at Montlhery and Italy lost its greatest star.

Despite his grief, the young Ascari’s resolve to race cars was merely strengthened, but there was a long wait ahead of him.

Time was when apprenticeship for the cockpit of a grand prix car was served on the saddle of a racing motorcycle, and Ascari spent four years on two wheels before an opportunity arose for him to make the switch.

In the 1940 Mille Miglia, a new marque appeared on the racing horizon. After many years of running a stable of Alfa Romeos, Enzo Ferrari had turned constructor. A legend was getting underway.

At the wheel of the 1.5-litre V8 Tipo 815, Ascari showed his class immediately, leading the race for a long time before the engine dropped a valve. The cognoscenti was impressed with this young man, but by now Benito Mussolini had plans for Italy that did not run to driving racing cars, and that was that for five years.

Italy being Italy, of course, motor racing got started again as soon as the last shot had been fired in World War 2. Monza was alive again! And back came the heroes, Luigi Fagioli, Carlo Felice Trossi, Luigi Villoresi, Giuseppe Farina, even Tazio Nuvolari, body riddled with tuberculosis, but spirit healthy as ever.

PLUS: The Ferrari ‘madman’ who pioneered dirty F1 driving

For Ascari, it was less simple. At this time, he was not committed as they were. At the outbreak of war, he had been on the threshold rather than at the centre of things. Several years had passed since that brilliant display in the Mille Miglia, and by now he had a wife and son.

His mother, a motor racing widow, hated it with a passion, and implored her son to put it out of his mind. So what to do? Ascari was in two minds.

From the outset of the 1949 season, it was apparent that Ascari no longer needed advice from anyone. In brief, he won almost every major race he started

Eventually, it was his great friend Villoresi who persuaded him to take it up again. All of his vast experience was passed on to Ascari and, as is so often the case, protege eventually left master behind.

In 1948, both men were members of the works Maserati team, and Ascari began to show the style and stamp that characterises all really great drivers. By the end of the season, it was obvious to Ferrari that he could not afford to have this man drive against him. It was probably the best decision the Commendatore ever made. This was an association that would last for five seasons, and one which brought Ferrari much success.

From the outset of the 1949 season, it was apparent that Ascari no longer needed advice from anyone. In brief, he won almost every major race he started.

The next two years were almost as successful, but the works Alfa Romeo team had a slight edge. All over Europe memorable battles were fought. This was a classic GP era, with Juan Manuel Fangio, Farina and Fagioli for Alfa Romeo and Ascari, Jose Froilan Gonzalez and Villoresi for Ferrari.

From this remarkable sextet, two men emerged – Fangio and Ascari – the greatest drivers of their time. Once in a while – such as Gonzalez’s day of days at Silverstone in 1951 – someone else would scoop the glory, but the basic pattern was never disturbed. Day in, day out, it was down to these two.

In 1952, however, it was all different. It was all Ascari. The GP formula had been changed, and now all world championship races were run for Formula 2, which had a two-litre capacity limit. Supercharging was banned. With Alfa Romeo gone, Fangio went to Maserati and Farina joined Ascari at Ferrari.

By now Ascari was at his peak, a near-flawless motor racing machine, almost an integral part of his Ferrari. Ascari and Ferrari: mellifluous words both, and for two seasons a virtual certainty for eight points – then the reward for victory – every time out. Ascari’s form, in fact, reduced GP racing almost to the level of farce. He made the business of winning races look absurdly simple.

Without him, the Ferrari team was not the same. Farina, Villoresi and Piero Taruffi all went well enough, but no more than that. GP races surrendered themselves to Ascari, and his rivals, thoroughly psyched out and demoralised, could do no more than squabble over second.

There were seven Grandes Epreuves in 1952 and Ascari won six of them, the other one, the Swiss race, going to Taruffi. Ascari didn’t win at Bremgarten because he wasn’t there… The race clashed with Indianapolis 500 qualifying and he was nominated for Ferrari’s attempt to conquer the Brickyard.

World champion in 1952 and 1953, Ascari shook the racing world by announcing his decision to leave Ferrari. The 1954 season would see the dawning of the new 2.5-litre Formula 1, and rumours were rife that Mercedes-Benz were coming back. Despite its 15-year absence from GP racing, no one doubted the German team’s ability to pick up where it had left off in 1939: winning.

But also coming into GP racing now were Lancia, and Ascari was tempted away from Maranello by the specification and potential of its car, the D50. Its designer was Vittorio Jano, the man responsible for the Alfa Romeo that had brought Antonio Ascari his greatest triumphs and had also taken his life.

Most people, however, were of a mind that the two-time world champion had made a big mistake. With Ferrari, after all, he was certain of a degree of success, so why change horses? But therein lies the answer.

Ascari had no interest in ‘a degree’ of success. Fighting for third or fourth was never his style. He wanted something that could run with Mercedes, and he was not sure that Ferrari could provide him with it. The Lancia was a completely unknown quantity, but the design was revolutionary, early power figures from the V8 engine were promising, and the car was tiny by comparison with its rivals.

In fact, 1954 was the most miserable season of Ascari’s racing life. For all its promise, the D50 was not ready to race, and its cursing driver had to sit out most of the year. Ascari and team-mate Villoresi spent a lot of time testing the car, confident of its ultimate potential but frustrated by a succession of maddening teething troubles.

Throughout all the tribulation and strife of 1954, his manner never changed. He was a modest man, unassuming, friendly and polite

The situation was ridiculous: the reigning world champion was absent from the circuits because his car wasn’t ready.

Lancia was hardly in a position to hold its man to his contract, but Ascari was a loyal individual and made no move to join another team. He did, however, have some freelance drives for Maserati and Ferrari, but nothing went right for him.

For the British GP at Silverstone, he appeared in a works 250F (below), but the car blew up soon after the start. One by one, the other Maserati drivers were called in to hand over to him, and all the cars came to the same sorry end.

As the last expired in a shower of metal and a cloud of steam, Ascari coasted into the pits. “Anymore Maseratis?” he asked, hopefully. “No more Maseratis,” was the sorrowful reply. Whereupon the great man got out, packed his bag and left before the end of the race. He had dominated the two previous British GPs. The situation was tragic.

Ascari, however, was never one to feel sorry for himself. In time, everything would come right, of that he was sure. And throughout all the tribulation and strife of 1954, his manner never changed. He was a modest man, unassuming, friendly and polite.

His popularity was immense but he never fell into the trap of believing his own publicity. Equally, he remained serenely unmoved by the ramblings in the Italian press, criticising his decision to leave Ferrari, doubting his ability to make the Lancia competitive, claiming he was past it. He recognised it for what it was: malicious drivel, written by precisely the same sort of cretins who described Niki Lauda’s decision to withdraw from the 1976 Japanese GP as that of “a trembling coward”.

For all Ascari’s easy-going manner, he was a very different proposition in a race car. His policy was exactly that later adopted by Jimmy Clark: lead into the first corner, put everything into two or three laps, leave the rest behind, demoralise them. When everything went to plan, both these men were virtually unassailable.

Conversely, neither relished a scrap. Leading a race, Ascari was the essence of calm and precision, with boundless confidence and faith in himself. In a wheel-to-wheel dice, though, he was less happy, less smooth, less quick. He hated to be behind another car, always giving the impression that he had to get by as soon as possible.

To see the set expression of Ascari in your mirrors was an unnerving experience. Once by, however, the precision and delicacy would return. He was a bindingly fast racing driver, regarded by many as quicker even than Fangio.

The year of 1954 was not without its moments of triumph. For one thing, Ascari won the Mille Miglia, an event he loathed. When signing with Lancia, he was adamant that the race should be excluded from his contract, but circumstances decreed otherwise.

Practising for the event, Villoresi (below left) crashed, putting himself into hospital for some time. In a gesture of loyalty, Ascari changed his mind and agreed to take part. The Mille Miglia had injured his friend, he said, and he wanted to square the account. Gianni Marzotto, who took second place, was more than half an hour behind…

Finally, right at season’s end, the maroon cars of Turin arrived at a GP. There was much at stake. The Italians had been banking on the presence of Lancia at Monza, but once again the entries were scratched. Now, at Pedralbes for the Spanish GP, two cars were rolled out for Ascari and Villoresi. The latter was no longer a frontrunner, and Ascari was well aware of the fact that a good, even a great performance was called for. Lancia was becoming a joke.

By the end of practice, there were a lot of red faces. Ascari, at his most ruthless and determined, had hurled the D50 through the streets of Barcelona in an exhibition of pure bravura. A clear second faster than Fangio’s Mercedes, the Lancia was on the pole. The men of Turin permitted themselves a smile. Whatever happened in the race, honour was now satisfied.

The handling of the car was a cause for concern, however. Incredibly unpredictable, it got through the turns in a series of twitches and lurches, Ascari fighting with the wheel all the way. Pole position flattered the car, but there was clear evidence that further development would make Mercedes sweat for its living. Further, there was proof, if proof were needed, that Ascari was as great as ever.

Somehow, Ascari got through the chicane but came out way too quickly, slammed straight through the straw bales and into the harbour

For the first 10 laps of the Spanish GP, the Italian humiliated the rest of the field, hustling away from them in magnificent style. And then the clutch began to slip. Ascari’s race was over, but he was a man refreshed, confident of great things in 1955.

The year began well, Ascari leading in Argentina until a spin put him off the road. Next came two non-championship races at Turin and Naples, and the Italian won both comfortably. Apparently, he was driving as well as at any time in his life, and the first European confrontation of Mercedes and Lancia was eagerly awaited. Monte Carlo. Another street circuit, like Turin and Naples.

The Lancia wound up second in Monaco qualifying [matching the pole time], splitting the Mercedes of Fangio and Stirling Moss. On race day, however, Ascari was unable to stay with the German cars and looked set for a safe third place.

At half-distance, Fangio retired but Moss was now almost a full lap ahead of Ascari. In the Lancia pit, they hung out the signals to the driver. Faster! At all costs, we must not be lapped! And Ascari, every bit as keen as they but now desperately short of brakes, charged on.

On lap 81, the entire pattern changed. Moss came to a stop with a broken valve, and Ascari was left with a huge lead. The jubilant Lancia pitcrew readied themselves to slow him but they never got the chance.

Out on the circuit, Ascari was still right at the limit, unaware of Stirling’s retirement. As he came into the chicane, the Lancia twitched sideways under the remains of braking. Somehow, Ascari got through the chicane but came out way too quickly, slammed straight through the straw bales and into the harbour.

The Lancia sank immediately, and there was no sign of the driver. The seconds dragged by and it seemed inevitable that Ascari had been knocked out at impact and drowned. Twenty seconds… then the familiar light blue helmet appeared on the surface, and cheering broke out as Ascari began to swim strongly towards a rescue boat. His only injury was a broken nose. It seemed like a miraculous deliverance, and so it was.

PLUS: The F1 moments that defined the 1950s

Superstition played an enormous part in Ascari’s life. He lived in terror of black cats, for instance. If he saw one crossing the road from the right, he would put off whatever he had in mind – unless, of course, another black cat happened to cross the road in the opposite direction! He had a horror of cabela, the omens of numerology. And he dreaded Montlhery, the scene of his father’s death 30 years before.

After the Monaco debacle, Ascari headed back to his family in Milan. Spa was only a fortnight away and he was determined to be fit. On Thursday 26 May – four days after Monaco – he decided to go out to Monza. Away from motor racing he felt restless, and Eugenio Castellotti, the Lancia team’s cub driver and something of a protege of Ascari’s, was due to test a Ferrari sportscar. After the morning session, Castellotti came in, joining Ascari and Villoresi in the paddock restaurant for lunch.

Afterwards, Ascari suddenly decided to do a few laps himself. It was a purely spontaneous decision. He had not taken his gear with him to the track, and was wearing a suit. Despite pleas from Villoresi, he was insistent on driving the car. After borrowing Castellotti’s helmet, he took off his jacket, climbed in and was gone.

He never came back. On his third lap, there was consternation back in the pits as the wail of the Ferrari was suddenly stilled and there was total silence.

Round to the scene they rushed, Villoresi and Castellotti, to the Curva Vialone where an appalling sight awaited them. Off the road lay the remains of the shattered Ferrari. Close by, Ascari was dying, and he succumbed before the ambulance arrived.

No satisfactory explanation for the crash has ever been found. One theory was that delayed concussion from the Monaco shunt had caused him to black out, another that his tie had blown up in front of his eyes, momentarily blinding him. There was even a wild story that Ascari had gone off the road to avoid a labourer working on the track. Mike Hawthorn’s feeling was that the tyres were at fault, that they were too wide for the rims, and that wheel and tyre parted company.

A great deal has been written about the series of eerie coincidences that linked the deaths of Ascari and his father. However sceptical one may be of the supernatural, there has to be a limit to what the word ‘coincidence’ may mean.

In Italy, and especially at home in Milan, the death of Alberto Ascari was a national disaster

Antonio was killed on 26 July, 1925, Alberto on 26 May 1955. Both were aged 36. Both lost their lives four days after miraculous escapes. Both men regarded their helmets as a lucky charm, and both were killed the first time they ventured onto a circuit wearing someone else’s helmet. Coincidence – and cabela – can be disquieting.

Ascari’s place in Italian motor racing has never been filled. There have been several good drivers from that country since. Luigi Musso, Castellotti, Lorenzo Bandini, but none with the sheer class of Ascari, none capable of beating all-comers. The only man with that kind of potential – Ignazio Giunti – was killed before his brilliance could come to fruition, and a great many people reckon that Italian racing died with Ascari.

They buried Ascari at the Piazza del Duomo and everything else in Milan was forgotten. The entire city was in shock. As the black coffin passed them by, a million people – yes, a million – took their last look at the familiar light blue helmet that rested upon it, and paid tribute to a man whose popularity transcended that of a mere racing driver.

In Italy, and especially at home in Milan, the death of Alberto Ascari was a national disaster.