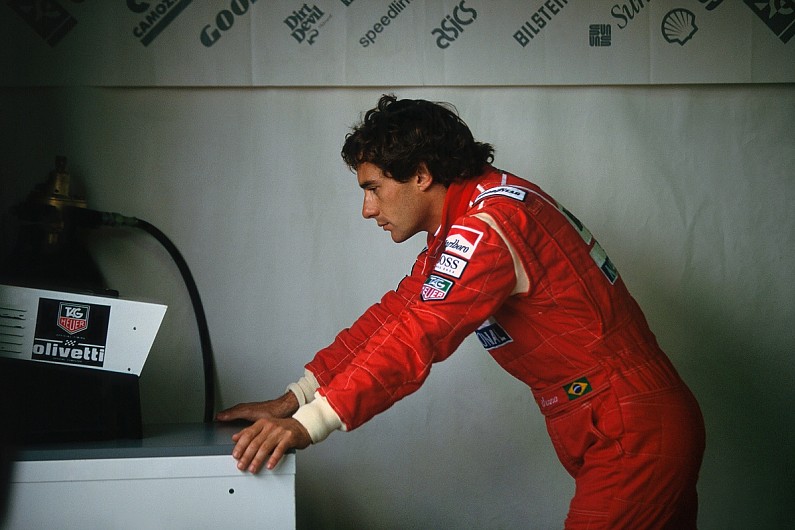

With Lewis Hamilton’s 2021 Mercedes Formula 1 contract finally resolved, it is worth recalling a similar story that played out 28 years ago – involving his hero Ayrton Senna.

Just as Hamilton held out in his discussions with Toto Wolff, so Senna went into 1993 without having signed a new McLaren deal with Ron Dennis.

When he finally signed the initial contract covered less than a third of the season. Only later would he agree to do the remainder of the races.

Throughout that year his participation each weekend was subject to a contractual clause that would keep McLaren’s legal team and accountants on their toes. If the team didn’t pay, Senna wouldn’t play…

“I remember it was a million dollars a race!,” recalls then McLaren operations director Martin Whitmarsh.

“In 24 and a half years I was at McLaren we were profitable in F1 and our other businesses every single year apart from 1992-’93, when we lost £1.5m, and we were paying Ayrton a million dollars a race…”

The delay in putting pen to paper was primarily a result of Honda’s withdrawal from the sport, announced at Monza in September 1992.

The season had already been a difficult one for Senna, with the latest Honda V12 proving disappointing, and Nigel Mansell dominating in the Williams-Renault.

Now McLaren’s post-Honda engine plans for 1993 remained fluid, and he was wary of going into the new season with a compromised package.

“As soon as Honda left, he didn’t want to continue,” says Whitmarsh. “Like any driver you want a works deal, and I think he was right.”

One plan was to buy Ligier, with Mansour Ojjeh’s help, and in effect asset-strip the French team’s customer Renault contract. That would at least provide some chance of taking on Williams.

That plan failed, and by early December it had become clear that McLaren would have customer Ford HB engines, although nothing was officially confirmed.

Commercially the switch from works Honda support to paying for Cosworths represented a huge shift for McLaren. Quite simply, there was less in the pot with which to pay Senna.

After winning in Adelaide he had disappeared to Brazil for his traditional off-season break with his family.

Then a few days before Christmas, and encouraged by his pal Emerson Fittipaldi, Senna travelled to Arizona to test a Penske IndyCar at Firebird Raceway.

He thoroughly enjoyed the outing, and made it obvious that Dennis couldn’t take it for granted that he would ultimately partner the incoming Michael Andretti in 1993.

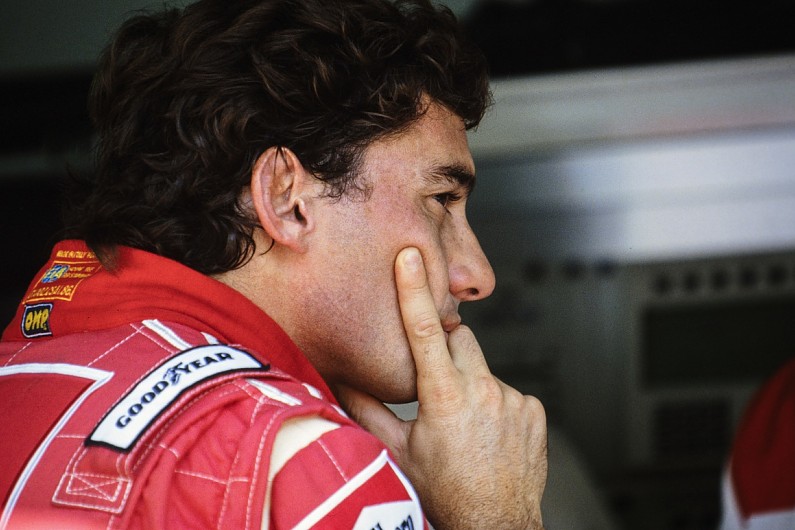

“I am not committed to any team yet because I’m seriously considering what I should be doing next and what’s best for my career,” he said after the test.

“That includes not driving in ’93 and thinking about Indy. I will now go home and have a quiet think about it and see what possibilities I can have for the immediate future.

“I must make it clear that there is no commitment from anyone regarding me driving in the future.”

Senna duly returned to Brazil to continue his break and have a proper think about his future. Along with his plans for 1993 he was also focused on the longer term, and how to get into a Williams for ’94.

Relations with Dennis were strained, despite their shared history of success.

“They were both highly intelligent,” recalls Senna’s manager Julian Jakobi.

“They were both pretty ruthless in what they wanted to achieve. They clashed occasionally. But fundamentally, they were reliant on each other for success.

“And it was a very good partnership, they actually got along very well. They fought their own corner. But they knew that they were better together than apart.”

Dennis meanwhile kept McLaren’s options open by signing Mika Hakkinen, who had impressed over two years with Team Lotus.

The Finn’s position was a little hazy. He could step into a race seat if no deal was done with Senna, but the risk was that former World Champion would return after all, and he’d thus spend a year as a test driver.

Dennis kept Hakkinen’s hopes up by suggesting that the team might be allowed to run a third car at some stage, and that one way or another, he would get to race.

However what the McLaren boss really wanted to do was sort things out with Senna, and eventually both parties met at the Swiss home of main sponsor Marlboro.

“Ayrton was a bit concerned about ’93, because McLaren only had a customer Ford engine,” Jakobi recalls.

“We had the first meeting in late January or early February in Lausanne at the Philip Morris offices.

“I flew into Geneva from London on a scheduled flight, and Ayrton flew private, I think he came from Brazil. Philip Morris sent to a car to pick us up at the airport, and we went to their offices.”

Senna and Jakobi duly took part in a meeting where the Brazilian’s future was discussed. Also present were Dennis, and top Marlboro marketing men John Hogan and Graham Bogle.

Senna had a clear idea of his market value, and knowing that his former team mate Gerhard Berger had signed a very lucrative deal with Ferrari, he was in no mood to compromise.

“It sort of came up that Ayrton’s retainer for ’93 hadn’t yet been agreed,” says Jakobi.

“Ron was having to pay for the customer engines. And he said that he only had $5m available, and therefore he couldn’t pay Ayrton what he’d paid him in the past.

“So Ayrton said, ‘That’s fine. I’ll do the first five races, and that’s it.’ And so that’s how the million per race happened. He didn’t say, ‘I want a million per race,’ he just said ‘I’ll just do the first five races.’

“There was kind of a silence in the room. And John Hogan started laughing and he looked at me. Graham Bogle didn’t laugh, he was the most serious guy out of them! And there was a silence from Ron.

“And then Ayrton said, ‘Well, if you find you have any more money later on, fine, we’ll discuss the extra races after the first five.’ So that’s what happened, the first contract was signed for five races, and a million a race.

“But we put a provision in the contract. Ayrton said, ‘But I’m not coming unless the money is in my bank account by the Wednesday before each race…”

Perhaps to Senna’s surprise the new Ford-powered MP4/8 was reasonably competitive in testing and in the opening race in South Africa, but it was still overshadowed by the Williams, now driver by his nemesis Alain Prost.

Then helped by bad weather and a little magic of his own he won his home race at Interlagos and the European GP at Donington. With rookie team mate Andretti struggling it was clear that McLaren needed every ounce of Senna’s talent.

Prior to round four, the San Marino GP, he played his contractual trump card. An opportunity arose to remind the team of his value.

“The first hiccup was in Imola,” says Jakobi. “I always had to confirm by fax or a phone call that the money arrived. Anyway, the money hadn’t arrived on the Wednesday, and Ayrton was in Sao Paulo.

“And so he said, ‘Okay, fine, I’m not gonna race this weekend then.’ And that was it, so I had to tell the team that he wasn’t coming, because the money hadn’t arrived. The team said they’d sent it – banking wasn’t quite as efficient in those days!

“Anyway, lo and behold, the money pitched up on Thursday morning rather than Wednesday.

“So I called Ayrton’s office in Sao Paulo, and they couldn’t find him. He gone off with some girl somewhere. He wasn’t in his apartment, he wasn’t in the office, and they couldn’t find him.

“And they found him Thursday lunchtime. So he jumped on the plane. McLaren sent Jo Ramirez to Rome to pick him up, but he went to the wrong airport.

“Ayrton got to the track late on Friday morning, got into the car halfway through first practice – and had an accident. So that was the first one that went haywire…”

He may have won two of the early races, but Senna remained frustrated that McLaren played second fiddle to works-backed Benetton in Ford’s pecking order.

His public complaints also served as something of a PR smokescreen, blurring the fact that the main reason for the ongoing “will he/won’t he show up?” saga was commercial.

Eventually Dennis committed to paying Senna for remainder of the 16-race season on the same basis as the initial batch of five.

“That’s why it was a million a race and $16m,” says Jakobi. “It was one contract, but it could be cancelled at any time if the payment didn’t come through by the Wednesday.

“Ayrton could give them a second chance on Thursday, but the option was his to cancel the contract if the money didn’t arrive. So effectively it was a race-by-race contact, because it could be terminated.

“The second contract was much more difficult to do than the first, because Ron was on the hook for $11m – and he didn’t have the money.

“And he had to get a guarantee or contract from Philip Morris, because Ron wouldn’t sign until he had it.”

A third victory of the season in Monaco was further proof of Senna’s value to the team, and after six races he actually led the World Championship, before Prost and Williams began to gather momentum.

Meanwhile Senna stuck rigidly to his principles.

“The second one was in July,” says Jakobi. “We were way beyond the first five races by then, so it was the second part of the contract, but still with the same clause – the money didn’t arrive, so Ayrton didn’t leave home.

“I think it was the French Grand Prix. Ayrton was due to fly from Sao Paulo to Frankfurt on Varig. His plane and his pilots were going to pick him up, and fly him to Magny-Cours.

“The money didn’t arrive, Ayrton said he wasn’t coming, so it was a major issue. I was in our lawyer’s office in London at midnight, and Ron was on the phone.

“We said Ayrton was not coming, because the money didn’t arrive by Wednesday. We prepared all sorts of drafts to terminate the contract, and so various drafts were circulating around.

“And Ron said ‘But you’re not going to do that anyway, because I know Ayrton’s on the plane. I’ve been informed he’s on the plane, and it has left Sao Paolo.’

“About half an hour later the phone rang, and it was Ayrton. We put him on the speaker. Ron was on the other phone and Ayrton said, ‘I’m still in Brazil, Ron.’ He said, ‘No you’re not, the plane left, you can’t be!’

“And Ayrton said, ‘Yeah, I am. I’m in Rio. I’m in the office of the head of police in the airport, and I’m not getting back on the plane until you confirm that that money is there.’

“What Ayrton had done was get the pilot of the Varig plane to stop off in Rio. All the other passengers were on the plane, and he got off.

“I think Ron gave a personal guarantee – I can’t remember exactly what it was, but we resolved it.”

After that glitch things ran more smoothly. Eventually Senna was confirmed as a Williams driver for 1994 – replacing Prost – and believing that he had secured himself the best car, he was able to enjoy his final races with McLaren. He signed off with a pair of wins in Suzuka and Adelaide.

“In ’93 his nemesis had 60 horsepower more than him,” says Whitmarsh. “When you are in the car and you reach the rev limiter at 10,500 or something and you hear a Renault at 13,000rpm, it must be a bit demoralising!”

“I think he always knew what the limitations were,” says Jakobi. “I think ’93 was his best ever season, in terms of the way he drove, even though he didn’t win the championship, because of the equipment he had.

“McLaren was still a very, very good team, but with an engine down on power. It wasn’t as good in ’93 as the Williams with the Renault.”