Mercedes hit the ground running when Formula 1’s turbo-hybrid era began in 2014, as its W05 made perfect use of the best power unit to charge to world title glory.

That championship was hardly a flash in the pan. Instead, the story of how Mercedes built on that early success with its subsequent cars offers a glimpse into how it has become dominant ever since.

Although its engine advantage was a significant factor in its performance edge in 2014, the German car manufacturer has never rested on its laurels when it has been ahead.

So rather than sitting back after being top of the pack, Mercedes’ High Performance Powertrains (HPP) worked in tandem with fuel and lubricant supplier Petronas to unlock even greater performance for subsequent years.

One area where teams looked to capitalise for 2015, was in an area that was not unlocked with the initial turbo rules – variable length inlet trumpets.

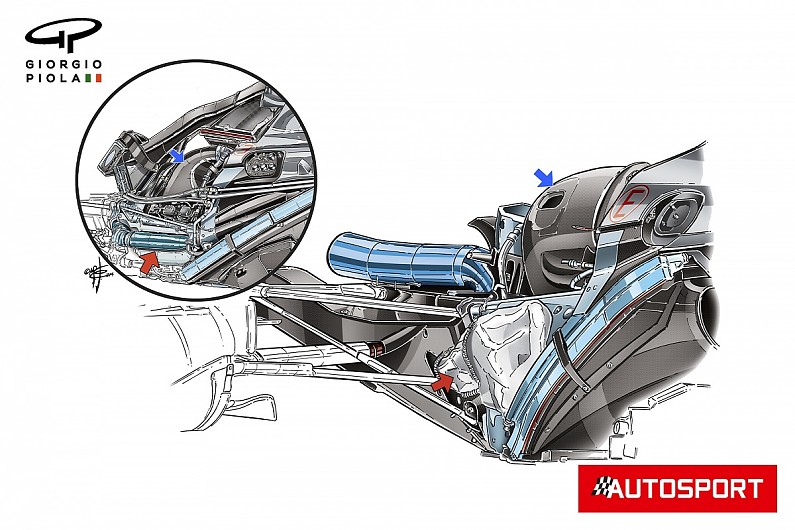

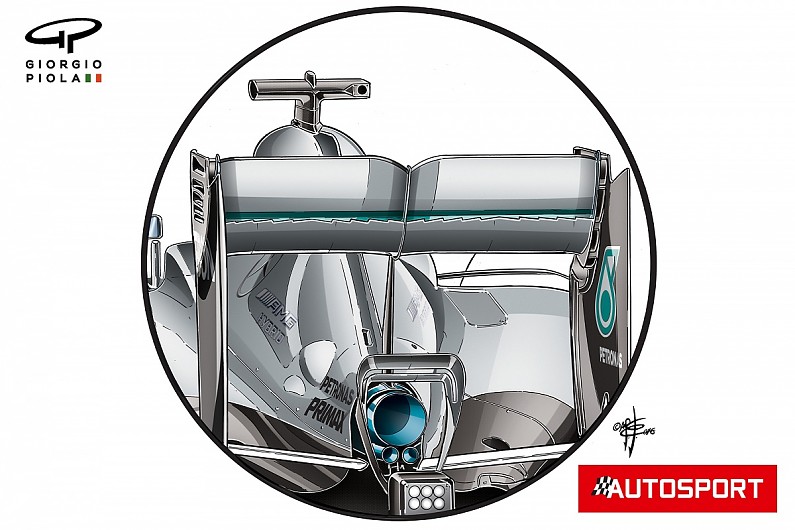

With an eye on extending its advantage, Mercedes repackaged the inlet manifold on the PU106B (blue arrow), whilst the log-style exhaust manifold used in 2014 (inset, red arrow) was replaced with a more conventional multi-branch arrangement, albeit covered here in this illustration by a heat shield.

Both would provide an uplift in driveability and overall performance, and would go on to form the foundation of the power unit’s DNA thereafter.

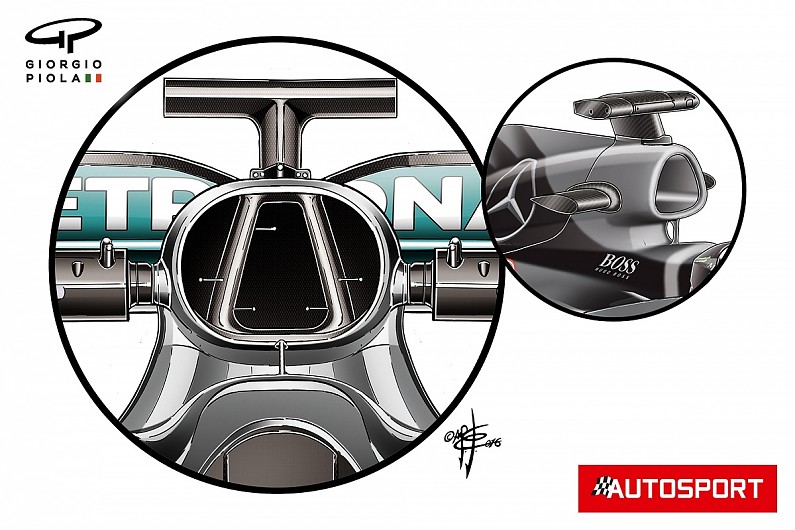

This was followed up in 2016 with a revised air intake design that laid the roots for the geometry used by the team over the last few years.

Seen below with the W06’s airbox in the smaller inset, we can see the team moved to a much larger oval airbox.

This was split by two diagonal spars that provide the integrity needed for the roll hoop aspect of the structure. This design not only allowed the team to feed the necessary airflow to the engine but also provided some headroom in terms of packaging.

That is because it allowed it to place many of the oil coolers associated with the power unit, ERS and gearbox centrally behind the main ICE.

This not only came with the advantage of having the bulk of the weight of its ancillary coolers on the car’s centreline, but it also tidied up the packaging within the sidepods too.

Aerodynamically the team had set its stall out with the W05, and felt that evolution over revolution was the best course of action. While much of the field had started to look more and more like the Red Bull, with its high rake philosophy, Mercedes plotted its own course at the opposite end of the spectrum with its W06.

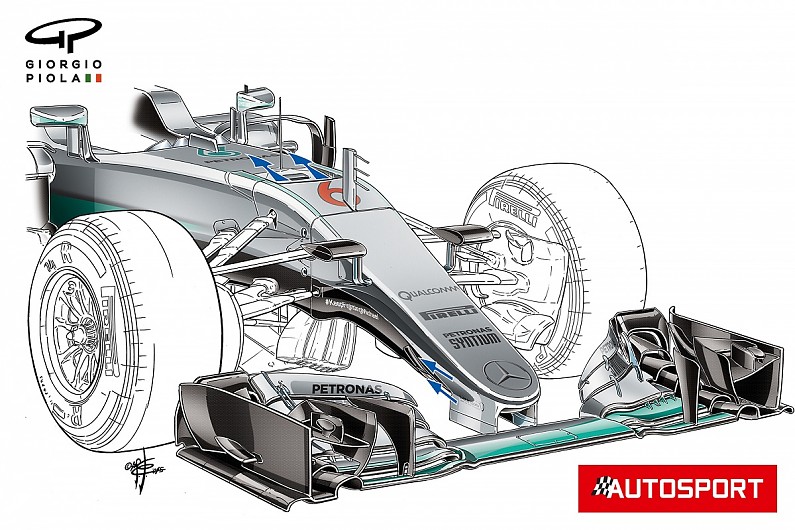

That’s not to say it wasn’t open to novel and interesting directions, with its front wing development resulting in the introduction of a squared-off tunnel design in the outer portion of the wing. This was dedicated to improving how the wing managed the wake turbulence by the wheel behind it, with this compartmentalisation of the outwash element continually optimised as it continued its search for extra performance.

Any alterations were also complemented by changes being made to the endplate, whilst the team searched for ways to improve the general performance of the wing too.

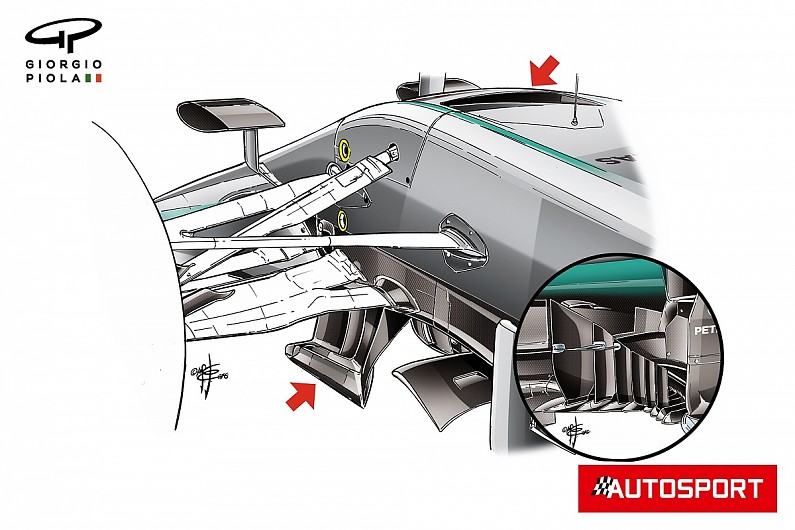

The W07 was treated to a revised endplate design, featuring two twisted sections at the rear of the surface, while a row of strakes were added to the upper flap as the team once again looked for gains with small aerodynamic features.

The regulations surrounding the nose were adjusted again for 2015, not only ruling out the unusual inverted U-shaped nose tip that Mercedes had used in its previous campaign, but also the swathe of ‘ungainly’ attempts by others in the field to use solutions that still filtered as much airflow under the nose as possible.

The Mercedes solution tapered from the chassis toward a narrow tip, with the wing pillars also placed inboard as a consequence. This is a design that evolved during 2016 to include an aerodynamic solution that many of its competitors had been using in one form or another since 2012, when Sauber reintroduced the ‘S’ duct.

The concept had been thought by many to be consigned to the scrap heap when Ferrari used a similar idea in 2008.

The advantage that the solution used by Mercedes had was that, unlike the one used by Sauber, it wasn’t restricted to having the pipework bound within a 150mm box section ahead of the front wheel centreline, taking advantage instead of the various regulations that had changed in that intervening period.

The inlet was placed much further forward on the W07’s nose, allowing airflow to be captured much earlier and perhaps at a point where the airflow was beginning to break down and separate.

The concept used by Mercedes therefore had much more in common with the original design used by Ferrari.

The idea, reanimated by Sauber in 2012, used ‘S’ shaped ductwork, hence the name, housed within a 150mm box section ahead of the front wheel centreline.

The team continued to build on the work it had done with its front suspension and steering arm from an aerodynamic perspective in 2014 too, as it moved the steering arm down inline with the lower wishbone, effectively widening its span.

Meanwhile, the turning vanes warranted further attention, with horizontal slots being added in the footplates in the first instance, before being replaced by longitudinal ones that divided the footplate into their own sections.

When solutions – such as the front-and-rear interconnected suspension (FRIC) are banned, teams don’t simply turn their backs on what they’ve learned: instead they use that knowledge to improve what will come next.

And, with Mercedes at the forefront of FRIC development when it was removed halfway through the 2014 campaign, its follow up was always going to prove potent.

It continued to develop hydraulic systems that improved the overall stability of the chassis, allowing its drivers to take more aggressive driving lines without adversely affecting tyre life, all the while aiding the car with a more compliant aerodynamic platform.

It’s perhaps worth noting that in light of the FRIC ban, Mercedes retained its hydraulic heave damper element, whilst most of the field used a spring solution, be it classically sprung or through Belleville springs.

Mercedes also continued its development assault on the bargeboard region, creating an extremely complex array that not only resulted in the main vertical element being split up into multiple segments – but also the footplate, which featured numerous finger-like extensions, reaching out from the front of the floor to help tidy up the flow being passed to the underside of the floor and diffuser.

At the rear of the car, the team had been working on finding the right aerodynamic balance for each of the circuits it visited, with the usual array of rear wing and monkey seats available for each.

An extension of its exercises with its front wing development, it also toyed with the use of serrations on the trailing edge of the mainplane to improve the performance of both elements.

The team also assimilated a design that we’d seen introduced by Toro Rosso a year earlier and had found its way onto many of their rivals cars since – open-ended endplate louvres.

The gap between Mercedes and its rivals was maintained during 2015 and 2016, leaving both Mercedes drivers to duke it out amongst themselves for the drivers’ titles.

Honours would be shared in that respect, with Lewis Hamilton taking the crown in 2015 and Nico Rosberg grabbing it the following year before his shock retirement.

But after three years of brilliance in F1 where its biggest headache had been handling the drivers, Mercedes was about to embark on a completely different experience as it subsequent cars behaved with some ‘diva’ like characteristics.