In cartoon land, Stirling Moss had a legendary team-mate in Skid Solo in the iconic Tiger and Speed comic book, which despite being fantasy loosely based on reality, drew far closer to the truth than anyone would foresee. ANDY HALLBERY looks back

The magical story Martin Brundle tells in this week’s Christmas issue of Autosport magazine about how he became Stirling Moss’s team-mate in 1981 in the British Saloon Car Series reads truly like a comic strip, a Boy’s Own tale.

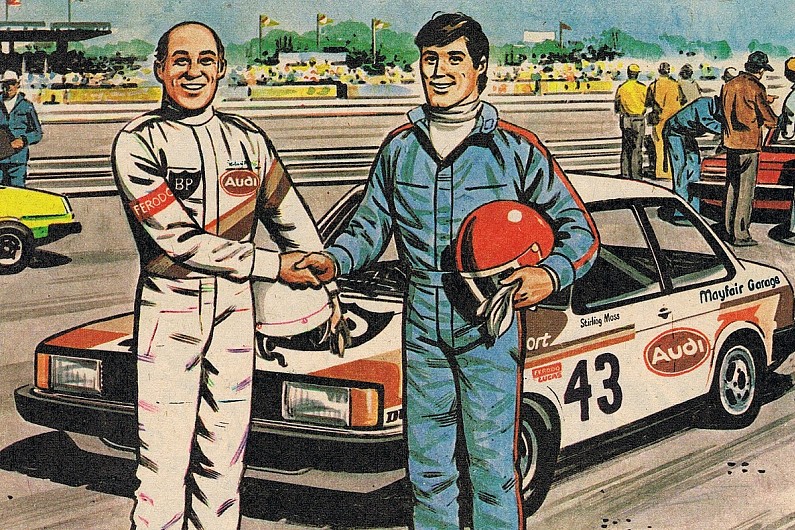

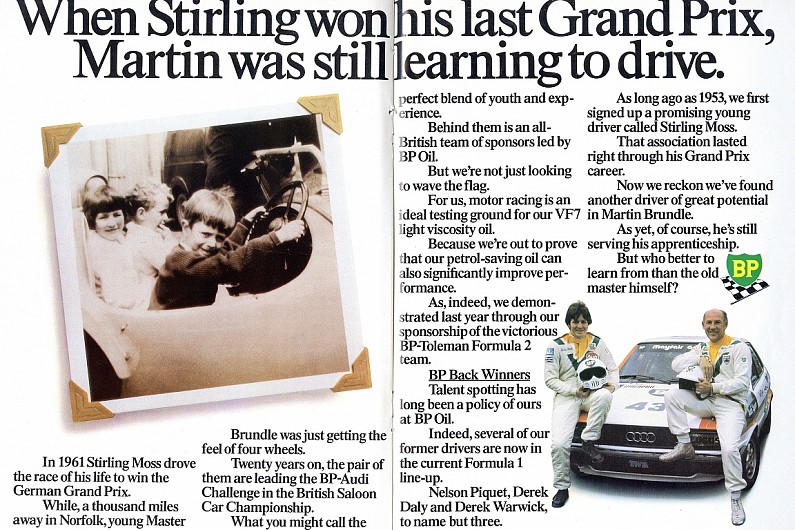

The 21-year-old was paired with Moss in TWR Audis, backed by BP. The oil company used the pair in an advertising campaign, which ran in Autosport that year, with an image of a four-year-old Brundle at the wheel of a toy car with his brother.

Brundle remembers the ad and both photos: “That first picture was taken from our West Lynn garage, which the agency never returned to my mum. I believe the second photo was the day I first met Sir Stirling at Silverstone – when we both got changed in the gents’ loos. Great advert though, although I was obviously saving up for a haircut.”

Meanwhile, simultaneously, in comic land, Moss became a regular in Tiger and Speed, only this time instead of being paired with Brundle in the Audi, Stirling was team-mates with the legendary Skid Solo, Tiger’s Grand Prix racing hero. Brundle laughs at the memory.

“I do clearly remember that. And I know I do, because just the mention of Skid is still current,” says the former grand prix driver and Sky Formula 1 commentator. “Even today I sometimes use the name ‘Mr S Solo’ for restaurant bookings! Skid was a bit of a legend, and it is good fun; it sums up the magic of the time really.”

So, who was Skid Solo? He started his F1 career in 1965 in Hurricane comic before Hurricane was absorbed into Tiger in 1966 and ran weekly until his forced retirement after a nasty crash in 1982, notching up 12 world titles during his 17-year career. Lewis Hamilton still has a way to go to beat that…

Skid missed a few grands prix over the years with various injuries – and even a kidnapping – but easily competed in more than 225 F1 races, as well as plenty of other racing capers. Tiger was a weekly, arriving Saturday mornings with the grown-ups’ newspapers.

Sharing the comic’s pages with Skid was another legend, footballer Roy Race of Melchester Rovers, in Roy of the Rovers among others.

The finished strips had to be at the printer six weeks before publication, and written and illustrated months before, which meant reacting to real-life was almost impossible unless they had a crystal ball

Barrie Tomlinson, editor of Tiger from 1969 until its closure in 1985, had learned the ropes on the comic Lion from 1961 and remembers the Skid Solo days fondly.

“The author was Fred Baker, who wrote many of the strips in Tiger, and it was drawn beautifully by John Vernon,” says Tomlinson. “At the start of each grand prix season I would get them the dates, and then we would talk about what was going to happen at each grand prix. When we published it, Skid would always be at the same race as the real-life grand prix that weekend.”

While that sounds simple enough, the finished strips had to be at the printer six weeks before publication, and written and illustrated months before, which meant reacting to real-life was almost impossible unless they had a crystal ball – which at times, they really did seem to have.

“It was exactly the same with the football stories,” continues Tomlinson. “Roy of the Rovers would be at the FA Cup or World Cup when it was playing. The World Cup was difficult because we never knew what colour the England shirts would be…”

This author began reading Tiger in 1974, and still has some copies that have not been opened in decades. Upon flicking through, one thing that struck me was how informative the Skid Solo strip was. As a kid, that’s where I learned what the numbers on a pitboard meant, what slipstreaming was and much more.

Indeed, decades ahead of its time, Skid’s long-time team-mate, the brilliantly named Sparrow Smith, suffered a concussion that was the topic of three pages explaining the effects of that and memory loss.

PLUS: Closing the knowledge gap on concussion

Then – amazing in retrospect for what was essentially a children’s comic – death. Yes. Sparrow died in a crash. It was a massive shock to read that on a Saturday morning in a comic that was usually fun. The message was simple. Motor racing is dangerous.

“We were going for realism,” explains Tomlinson. “One of the things at the time was to try and make it as realistic possible, and follow what was happening in the real world. There were a lot of crashes in those days, weren’t there?”

Back to that crystal ball. In the Tiger that dropped through letterboxes on Saturday 31 July 1976, Skid’s main rival, German racer Von Vargen, crashed and caught fire at the Nurburgring after his right rear wheel came off. The very next day, Niki Lauda was on the TV news having his almost identical fiery accident… And that was not the only time Tiger art predicted real life.

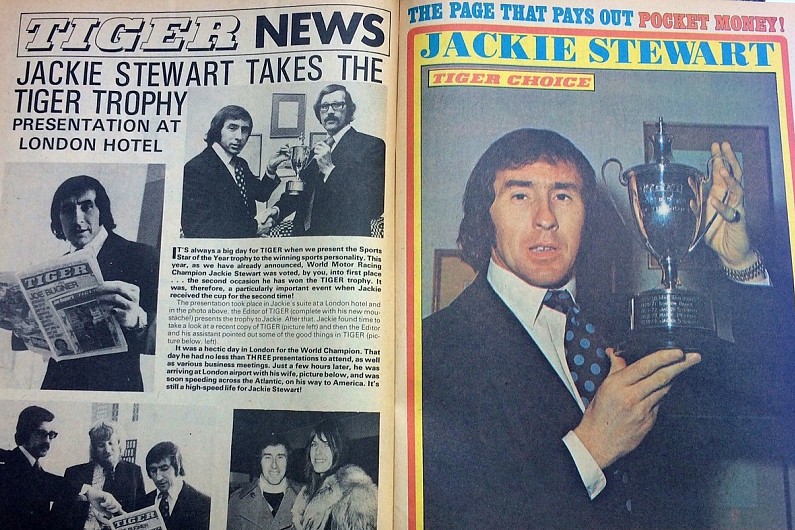

Tiger also had many sporting heroes as fans. Besides Moss, other champions graced its pages, too. The Tiger Sports Star of the Year Trophy was won by both Jackie Stewart (twice), and James Hunt, and on each occasion they collected the trophy in London. Pele, Barry Sheene, Geoff Boycott, plus a variety of champion footballers, cricketers and boxers regularly posed for photos while reading a copy of Tiger.

In 1982, Skid had a new car and was leading at Imola when on lap five something failed on his car. The resulting crash ended his career – and the strip in Tiger for good. Sudden isn’t a strong enough word. By now 15 years old, this author was devastated that his comic ‘hero’ wouldn’t be landing on the doormat anymore.

“That was one of the toughest decisions that I had to make,” says Tomlinson. “And then to contact John Vernon and say, ‘I’m sorry, we are going to have to drop Skid’. It was really difficult as I knew John very well, and he’d always done a good job.

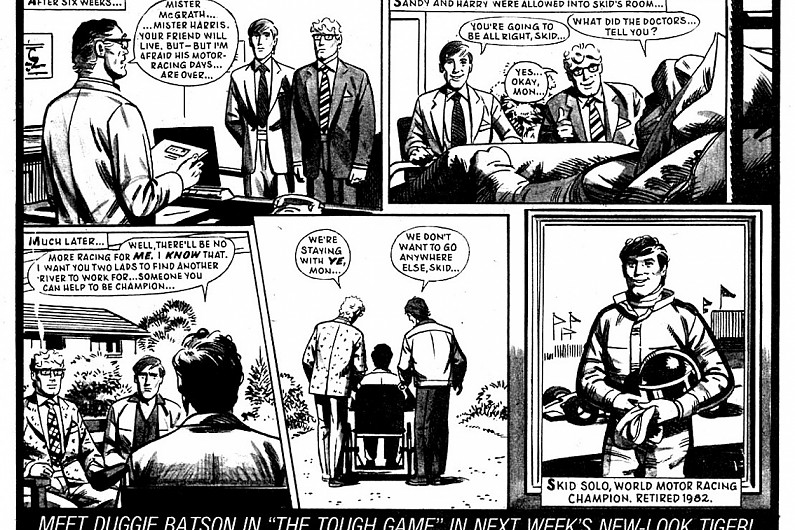

The three-page strip goes from the start of the grand prix and pictures Skid’s accident, but you never see his face again. He’s in hospital for weeks, and the last frame is him in a wheelchair from behind

“As for it being very abrupt, it was actually my choice,” he continues. “Skid had been very popular, but it was going down, and I knew that I had to drop it. We decided that rather than him fade away we’d do it in a dramatic way.”

The three-page strip goes from the start of the grand prix and pictures Skid’s accident, but you never see his face again. He’s in hospital for weeks, and the last frame is him in a wheelchair from behind. It was the end of an era, both real and imaginary.

Seven days later, the racing world was devastated by the loss of another racing hero, with Gilles Villeneuve at Zolder. That real-life crystal ball was in effect again.

Oh, and the issue date of Skid’s career-ending 1982 crash at Imola’s first turn? It was 1 May, the same date on which Ayrton Senna was killed 12 years later at the same corner.

Many thanks to Barrie Tomlinson for his help in researching this article and for giving the world Skid Solo and Tiger comic from the 1960s to ’85. Also to @YeOldeAutosport for locating the BP ad and to Tim Wright at Motorsport Images