Fifty years on from the first of Al Unser’s record-matching four Indianapolis 500 triumphs, Autosport’s IndyCar correspondent DAVID MALSHER-LOPEZ recalls the career of an Indy hero

No fan of the Indianapolis 500 needs telling that last weekend was a weird one. For media folks – who are merely fans paid to write about it – a Memorial Day weekend without any racing activity at the Brickyard was very different too.

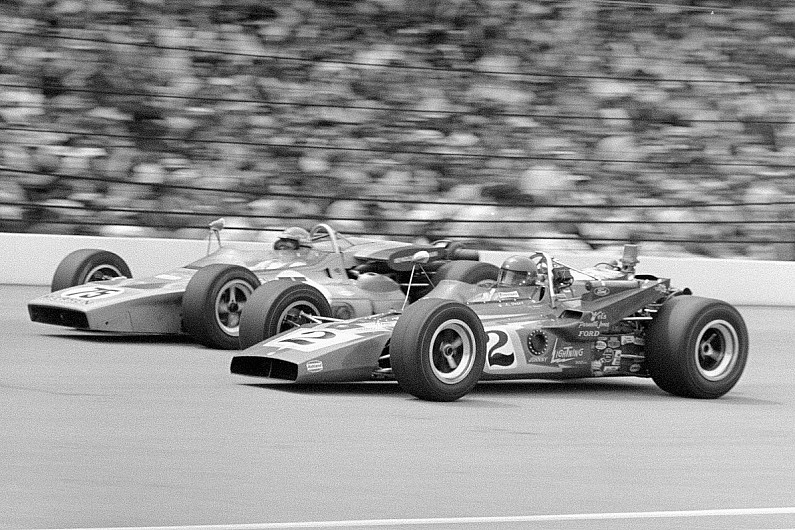

Among the many pleasures of two and a half weeks at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway during the month of May is the chance to wear the latest Robin Miller/Steve Shunck-commissioned sweatshirts bearing ‘anniversary’ cartoons by the great Roger Warrick. One of this year’s celebrates 50 years since the great Al Unser in the Colt-Ford ‘Johnny Lightning Special’ scored his first of four 500 wins.

A driver equally as comfortable on dirt as a paved oval or a road course, Unser was still winning at Indy 17 years later and even beat his son Al Unser Jr. to win the third title of his remarkable career in 1985.

Unser, who finally retired in 1993, once told this writer that he’d trade all three of his series titles to have another Indy 500 victory. Nevertheless, he still lies fifth in US open-wheel’s race-winner list (39) and tenth in the pole-winner list (27). Meanwhile, at his beloved IMS, as well as his record-matching four triumphs (an accolade shared with AJ Foyt and Rick Mears), Unser holds the record for most laps led (644), is fifth for most races led (11), holds the record for longest gap between first and last wins (1970 and 1987), and retains the record for oldest winner aged 47 years and 360 days.

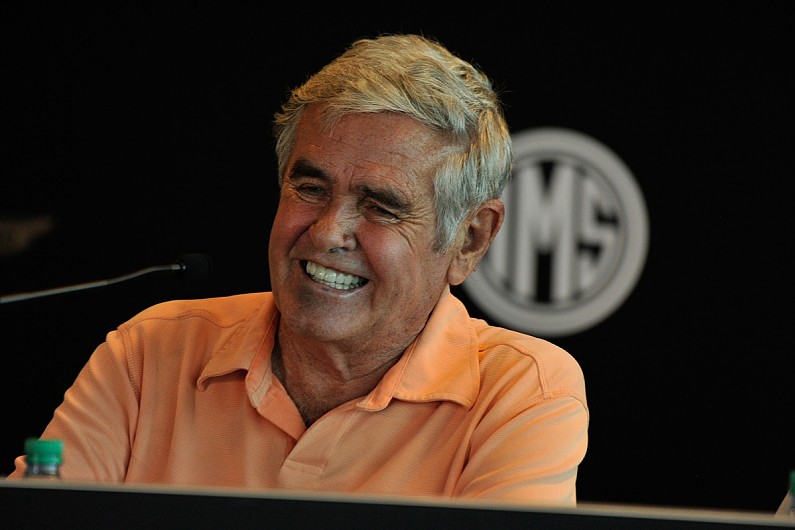

Unser, now 81, remains a quiet man, shy and genuinely introverted but one who had to reluctantly accept that his ability and results rendered him a superstar.

Rise of a champion

Seven times an engineer of the Indy 500-winning car, legendary crew chief ‘Big Nutz’ George Bignotti was renowned for regarding things in black and white – his way and the wrong way – and in retrospect it’s a surprise that he and Foyt lasted six years together. Mind you, success is a super salve for wounded feelings and, together from 1960-65, they scored three championships and 27 wins, including two Indy 500 victories in 1961 and ’64.

After Bignotti, who died in 2013, ran Formula 1 ace Graham Hill to victory in the 1966 Indy 500 for the Mecom Racing team, he needed a full-time Foyt replacement who was mechanically empathetic, listened to advice and had the talent to follow that advice.

Unser, who had made his Indy 500 debut in Foyt’s back-up Sheraton Thompson Lola in 1965 and won that year’s Pikes Peak hillclimb, fit all those criteria and was duly hired by the Mecom team under the banner of financial backer Al Retzloff.

“In ’67, I finished second behind Foyt. Yet the next day, someone asked me where I had finished. I was amazed!” Al Unser Sr.

“I would say it took Al about a year to really get in the groove,” the late Bignotti (below, crounching beside the right-front corner of the Johnny Lightning Special) said of Unser. “But once he started winning, boy! It was like he was winning everything.

“He was a very smooth driver. You didn’t see him thrashing the car when he was going flat-out. He came through the field until suddenly, when you looked up from your lap chart, he was there in the lead!”

Bignotti was right. The younger brother of Bobby Unser, who would himself go on to win the 500 three times and was already making waves in Indycars, Unser would score nine runner-up finishes between 1966 and ’68 before scoring five straight USAC wins spread between Nazareth, Indianapolis Raceway Park and Langhorne.

But Unser had already been made aware that success at Indy, the amphitheatre that had claimed the lives of his uncle Joseph in 1929 and his brother Jerry in 1959, was everything.

“In ’67, I finished second behind Foyt,” he recalled more than 30 years later. “Yet the next day, someone asked me where I had finished. I was amazed! That taught me there’s only one place, and that’s number one.”

Reflecting on his early experiences at the Speedway, Unser admitted he “got goosebumps on the grid” at his 1965 debut.

“It was a feeling of success just to be there already,” he explained. “First, you have to get the opportunity to go, then you have to pass the rookie test, then you have to qualify. Each is a very big stepping stone. There are many drivers who never got the chance to go, many who never pass the rookie test, many who never qualify.

“You might you have the ability, but you don’t really until you’ve done it. But once I had made it to the race that first year, then I wanted to finish it, which I was able to do. Then I wanted to finish the race well up. Then, of course, you always want to win it. And by then you’ve got that sensation of, ‘Gee, I’ve really done .’ To compete against your idols and then finally beat them is a sensation that is unbelievable.”

Before that, however, he had to suffer the mortifying experience of missing a prime chance of success. Retzloff had left racing in 1968 and his assets – including Unser and Bignotti – had been bought up by Vel’s Parnelli Jones Racing, run by Vel Miletich and 1963 Indy-winning driver Parnelli Jones. The following May, Unser was fast in a Bignotti-modified all-wheel-drive Lola T150 throughout practice, but during a rainout he fell off his motorcycle in the infield, broke his leg and had to miss the race.

Unser would be out for six weeks, but was then anxious to make amends for his gaffe. A win at the Milwaukee Mile in the turbocharged car was swiftly followed by two victories in the dirt car – in the Ted Horn Memorial at Du Quoin and the California State Fairgrounds Sacramento 100 – another in the normally aspirated Lola at Pacific Raceway in Washington and a further triumph in the turbo version at Phoenix. Remarkably, therefore, despite missing three rounds, Unser finished second in the 1969 USAC championship to runaway winner Mario Andretti.

Carrying that momentum into 1970, Unser won the season opener at Phoenix, while the car for Indy was so heavily re-engineered by Bignotti and rebodied by ace aerodynamicist Joe Fukashima that it warranted a new name – the Colt 70. Sponsorship from Topper Toys, which was attempting to steal a marketing march on Mattel’s Hot Wheels series, rendered the Colt-Ford the ‘Johnny Lightning Special’. A legend was born.

Unser took pole, but only by 0.003 seconds, after a particularly brave effort from Johnny Rutherford in an Eagle. Bignotti remembered Unser’s effort as a result of he and his driver being on exactly the same wavelength.

“In 1970, there had been no rain for the month of May so far, so the track was real greasy by the time we got to Pole Day,” said Bignotti. “I’d been listening to the on-track commentary and I’d hear a driver say things like, ‘My car had so much push I don’t know how I was getting through the corners’, and each time I heard this I would adjust our suspension some more.

“Eventually, it came to Al’s turn, and I said to him, ‘Be careful of it getting loose on that first lap, the second and third laps should be fine, and then on the fourth it’s going to be understeering like crazy.’ He listened, acted upon what I had said, and put it on pole.”

If qualifying was close, no-one else was truly in the running on race day, and Unser led 190 of the 200 laps, matching Jimmy Clark’s effort in the Lotus from five years earlier.

“You never you will win Indy,” he said. “There isn’t a driver who can ever say that. But even before practice started we knew if we did everything right, we had a very good chance of running up at the front. But we didn’t know we could lead the amount of laps we did.”

Unser went on to win the 1970 championship, five triumphs in the Colt being backed up by five more in the King dirt car.

As is the way in racing, however, the opposition spent the off-season whittling away the VPJ team’s advantage and, when McLaren came forth with a striking new development of its M16s, Unser, Bignotti and co were suddenly on the back foot.

“McLaren should’ve beaten us,” says Unser of Memorial Day in 1971. “They had a ten-times-better car, because their interpretation of the rules produced a huge rear wing and lots of downforce.”

Triumph against the odds followed by struggle

Qualifying revealed all: Peter Revson’s works McLaren took pole at 178.69mph, Donohue’s Penske-run McLaren was second; Unser lined up fifth in the reworked Colt 71, unable to break the 175mph barrier. Consequently, Unser draws far greater gratification from his second consecutive triumph at the Speedway.

“Revson and the McLaren team just didn’t know what they were doing. They lost that [1971] race on sheer inexperience” Al Unser Sr.

Donohue pulled away from everyone until quarter-distance, when his transmission failed, and that should have left Revson with an easy win. Instead, he didn’t even lead a lap.

“We led over half the race that year,” Unser chuckles. “Revson and the McLaren team just didn’t know what they were doing. They lost that race on sheer inexperience. It was a more satisfying win than the year before, because in ’70 we knew we could do it, which created pressure, but a different sort.

“In ’71, we knew we’d have to work incredibly hard and make everything count for us. That was a hard, hard day with the right result.”

Following another triumph at Milwaukee the following week, Unser’s year would dwindle away with a spate of DNFs and he’d finish only fourth in the championship.

The following year, Miletich and Jones would run three cars for Unser, Mario Andretti and Joe Leonard and hired Lotus 72 designer Maurice Phillippe to pen the new car. Bignotti’s influence on the team’s output was further reduced when it was decided that engine tuning would be the job of an outside company.

“That’s when the nightmare started, when that ‘creation’ happened,” recalled Unser of Phillippe’s strange device (pictured below) that bore two 45-degree wings mounted halfway between the rear axle and cockpit.

“I knew that dihedral wing car wouldn’t work. I finished second at Indy in ’72 but, if it had been the car it should have been, I might have given [winner] Donohue a decent run.

“There was Joe, Mario and myself and we were working for Parnelli, so it was being called ‘The Super Team’ and so on. Well let me tell you, there was nothing super about it.”

Bignotti, feeling marginalised despite helping Leonard win the 1972 USAC title, left at season’s end, but although he was annoyed he admitted he had enjoyed his working relationship with Unser.

“Al would never complain about the car,” he said. “He wasn’t the sort of guy to come into the pits and say, ‘Change these springs, do this, do that,’ which is good, because those sorts of things don’t go over too well! He would just tell me precisely what the car was doing, and I knew exactly what to do from what he was telling me about how the car felt. Then he’d go out and set his fastest lap.”

Unser stayed aboard the Super Team, and his inability to take more than a solitary win in 1973 would help persuade VPJ to switch to customer Eagles in 1974 and 1975. But Al was never convinced that he had the exact same-spec car as his brother Bobby did in the works Eagle team, and he added only more win in two years.

So he was more than happy to learn that for 1976 VPJ was switching back to creating its own designs, especially when a youthful John Barnard – hot off some fine updates to the McLaren M16 – helped to ensure VPJ-6B was a winner. Over the next two years, Unser suddenly looked a force again at Indy, third place in 1977 his best result. He racked up four victories and finished second in the points to Tom Sneva in 1977, but the relationship had run its course.

“Vel and Parnelli started doing things I didn’t like, so I quit,” he explained somewhat vaguely. “Parnelli and I are still good friends, and he was a great car owner, but at the time I was tired of it. I had to move.”

A new chapter at Chaparral

Unser joined Jim Hall’s Chaparral squad for 1978 and was at his finest at Indy, securing a third win despite a slight pitlane error when he bent his Lola’s front wing against a tyre on his final stop.

“You can tell a car has a basic handling issue when it burns off tyres too quick whatever the track – except the superspeedways” Al Unser Sr.

“Actually, I didn’t know I’d hit it till later; it didn’t affect the handling at all!” he laughed. “Sometimes, when it’s your day, it’s your day. Earlier in the race, I don’t know whether I gained the speed or my rivals lost it, but all those cars just backed up to me.”

It was the first of three superspeedway wins for Unser that year, giving him the still unique Triple Crown of 500-mile Indycar races in one year – Indy, Pocono and Ontario Motor Speedway. Elsewhere, however, the appropriately named Lola T500 was one he found very disappointing.

“It wasn’t too reliable, for one thing, and to get results you need to be there at the finish,” explained Unser. “But I also felt it didn’t handle well off of tighter turns on short ovals. I could have it so it was uncomfortable to drive and fast, but… it didn’t feel like that came natural.

“It’s difficult to explain, but you can tell a car has a basic handling issue when it burns off tyres too quick whatever the track – except the superspeedways. The other reason it worked in those 500 milers is because the race was long enough for us to work on it and improve it each time we hit pitlane.”

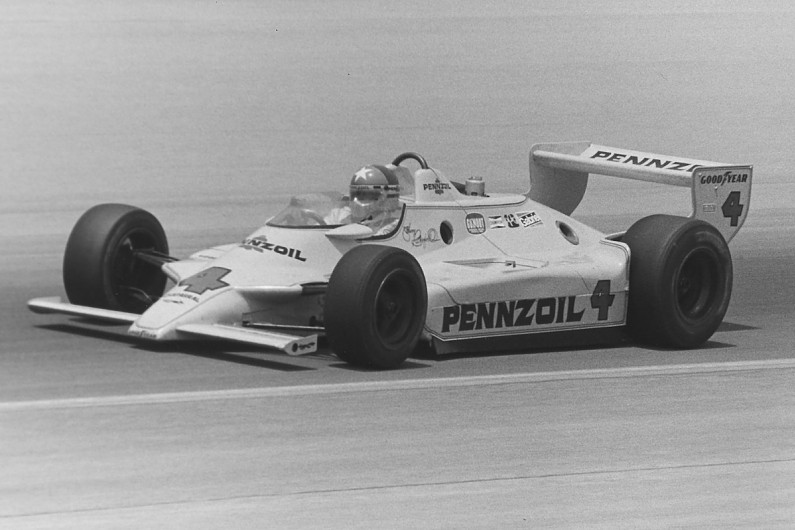

That summer, Unser and other ex-VPJ guys such as ace chief mechanic Hughie Absalom persuaded Hall that he needed to hire Barnard if the team were to quit running customer cars and return to Chaparral’s tenet of progress through innovation. Barnard’s beautiful Pennzoil-sponsored ground-effect 2K was the result, and Unser caned everyone on its race debut at Indy in 1979 until an oil leak caused the transmission to seize at half distance.

Throughout the year the car’s huge potential went unrealised until finally, at the season finale at Phoenix, the ‘Yellow Submarine’ earned its first victory. But Unser’s relationship with Hall had deteriorated and, being a fan of Barnard, he hadn’t liked the way the young Englishman’s ingenuity on the 2K had been downplayed.

With not only Barnard but also engine expert Franz Weiss heading for the exit, Al didn’t like the way things appeared to be heading which, with hindsight, was to prove a mistake. To this day he insists he has no regrets about departing the team at the ‘wrong’ time, but the fact remains that he handed the keys to the best car in the paddock to a grateful Rutherford, who would win Indy (below) and the CART Indycar title in 1980.

Unser, meanwhile, endured three fruitless and frustrating years with the new Longhorn team, helping its owner, Texan oilman Bobby Hillin, chase his brave albeit brief dream of Indycar success. Unser came close several times, but two second places were a poor return.

Revival at Penske

Once the Longhorn project folded at the end of 1982, Unser departed for Penske and in 1983 promptly won his first championship since 1970. An underrated road racer, he triumphed at Cleveland and finished in the top five nine times, four times as runner-up, to see off a late challenge from star rookie Teo Fabi.

While 1984 was a washout by contrast – finishing ninth with only two podium visits – team-mate Mears’s dreadful ankle-pulping shunt at Sanair persuaded Roger Penske to retain Unser for 1985, and he repaid the gesture by winning the title again.

But, now in his mid-forties, he was aware it was time to throttle back to a part-time gig, especially now that Mears was back to full strength in 1986. At year’s end, Unser’s driving career appeared to be over, aside from some Indy-only opportunities. The one he didn’t expect came from Penske the following May.

Already alarmed that for the second straight year his design team had created a dud, forcing yet another switch back to customer March chassis, ‘the Captain’ had a further hurdle to overcome when, during Indy 500 practice in a third team entry, Danny Ongais put himself into the wall and into the hospital for the rest of the month.

“I let Mario Andretti lap me after about 20 laps. And that’s when I got pissed off” Al Unser Sr.

Full-timers Mears and Danny Sullivan (the 1985 Indy winner) would qualify their Chevrolet-powered Marches in third and 16th but, to replace Ongais’s smashed machine, Penske famously dragged an exhibition car from a hotel lobby in Reading, Pennsylvania and fitted it with a Cosworth DFX. It was an unlikely pick for Unser’s fourth and last Indy win, particularly when he qualified 20th and had to take evasive action on lap one.

“Josele Garza spun in Turn 1 and almost put me in the wall!” said Unser. “That’s always the problem with starting back there, and over the years I’d tried to avoid that by qualifying at the front, among the quick and experienced guys that you can trust. Garza’s car actually touched mine, and I said to myself, ‘Man, it’s gonna be one of those days.’

“So I took it easy, too easy. I let Mario Andretti lap me after about 20 laps. And that’s when I got pissed off and went after him. There’s no way I could have beaten him that day. He had us covered – had the whole field covered – but he never lapped me the rest of the race.”

But with just 20 laps to go, having led for 170, Andretti dropped out when his engine blew.

“That left me and Roberto Guerrero going at it for the win,” said Unser. “Roger had been on my radio since Mears had gone out, so I knew I was running good enough. Roger tells you who’s around you, what you’re doing, what others are doing – actually, he never shuts up.

“Anyway, it was very even between me and Guerrero: if I was ahead of him, I could stay ahead; if I was behind, I couldn’t pass. Then Roger made a decision to make our final pitstop early to put pressure on Guerrero, and that’s exactly how it worked. He messed up in the pits.”

For the next two years, he qualified a Penske on the front row; he also coaxed a Lola-Buick to finish third in 1992 (below), the year Al Jr. finally won the 500; and the 54-year-old even led the race a couple of times in King Racing’s Lola-Chevy in 1993. But the decision to retire altogether was swift the following year.

“I found myself standing on the pitwall watching my son qualify and suddenly realised I was too interested in how he was doing,” says ‘Big’ Al. “People who lack the ability to give 100 per cent don’t win. So I quit.”

And he did so as an Indianapolis Motor Speedway and Indycar racing legend.