The F-duct device pioneered by McLaren during the 2010 Formula 1 season was a novel way of reducing drag that was swiftly copied and then quickly banned for 2011.

When McLaren unveiled its new MP4-25, it hoped that its new mechanism – known internally by its project number RW80 – would fly under the radar.

But secrets rarely last long in the fast-moving grand prix paddock and its controversial solution – dubbed the “F-duct” owing to the letter in the Vodafone sponsor logo next to the chassis inlet – inevitably captured the imaginations of fans, media and teams, which quickly rushed to work out a means of adopting their own devices.

While undoubtedly effective and certainly innovative – winning McLaren the Pioneering and Innovation Award at the 2010 Autosport Awards – the F-duct couldn’t make up for deficiencies in the MP4-25, which still won five races in 2010 with Lewis Hamilton and reigning world champion Jenson Button.

Despite Red Bull’s late adoption of the F-duct, its mastery of the blown diffuser effect proved potent enough to offset its disadvantage and it swept to the drivers and constructors championships.

The F-duct’s lifespan was short-lived – voted out on cost and safety grounds in a meeting at the 2010 Spanish GP – and duly replaced with the Drag Reduction System for 2011.

How did the F-duct work?

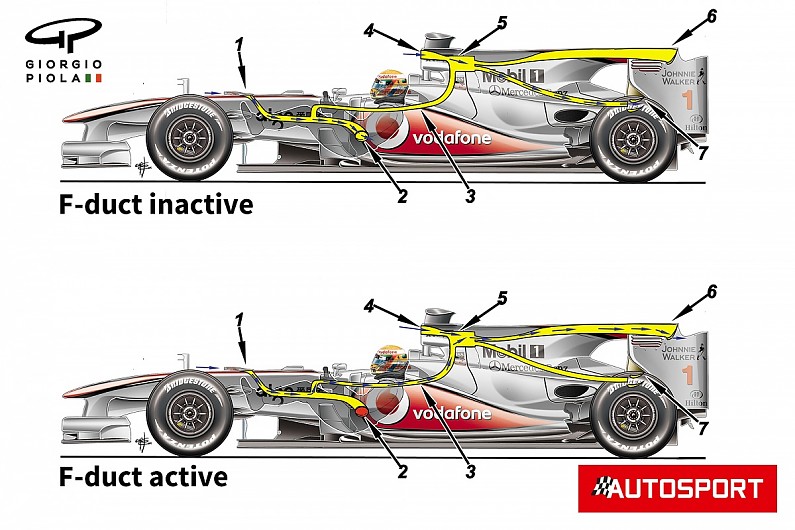

The system, which consisted of numerous pipework channels, was operated by the drivers on the straights in order to ‘stall’ the rear wing, reducing downforce and drag that produced a straight-line speed advantage.

When the cockpit hole [2] was uncovered, airflow taken in by the chassis snorkel [1] would flow through into the cockpit [2], whilst airflow taken in at the airbox would be fed through the fluidic switch [5] and out through the neutral engine cover outlet [7].

However, when the driver covered the hole in the cockpit, the airflow captured by the chassis inlet [2] would bypass the cockpit and travel through the signal pipework [3] to the fluidic switch chamber.

Once here, it would divert the airflow from the airbox [4] to the upper pipework and deliver it to the rear wing [6]. The airflow would then be fed out of an additional slot in the rear face of the wing, interrupting the airflow on the wing’s suction surface and producing the stall.

McLaren’s system went through various iterations throughout the season in search of more performance.

The cockpit hole that the driver used to operate the system was initially covered by the drivers’ knee, but a later version featured pipework moved further into the cockpit to allow the drivers to use their elbow.

Meanwhile, the snorkel inlet on top of the chassis was redesigned several times to improve flow into it.

The level of downforce and drag reduction required for each circuit also meant that McLaren had different options available to it at either end of the spectrum.

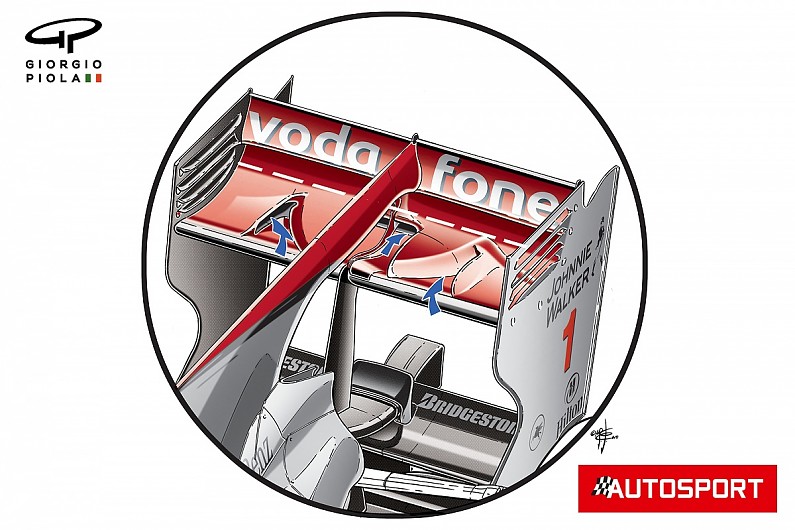

For Monaco, the team using supplementary inlets and outlets in the rear wing mainplane (pictured below), whilst at Monza it split its strategy, with Hamilton lamenting his decision not follow Button’s lead and keep the F-duct as he could only qualify fifth and was eliminated in first lap contact with Felipe Massa’s Ferrari.

The team also made a revision to the entire rear-end of the assembly in Japan, following Force India’s path of connecting the ducts to the mainplane rather than the top flap to produce a greater stall effect. This resulted in the corresponding slot on the rear face of the wing being moved too.

Despite the rules prohibiting driver-induced aerodynamics, the FIA did not prevent the F-duct’s development.

But as teams faced difficulties incorporating it into homologated chassis, and with questionable designs emerging that required drivers to take their hands off the steering wheel to activate it, there could be little surprise when the concept was banned and replaced with the hydraulically activated DRS systems that remain today.

However, a variation on the F-duct would return in 2012 with an FIA-approved Mercedes DRS design the subject of much controversy early in the season, although its then technical director Ross Brawn was adamant that the solution couldn’t be illegal as F-ducts hadn’t been properly defined in the first place.

Rivals construct their own ducts

Sauber was the first team to follow McLaren and introduce its own version of the F-duct system, arriving at just the second round of the championship in Australia.

The Swiss outfit’s design differed from McLaren in several ways, with the snorkel initially placed on the sidepod, rather than the chassis – before moving to a position more similar to McLaren’s to allow the drivers greater control over the system. The rear wing feed and rearward slot was on the mainplane rather than the top flap too.

To stabilise flow around the rear wing, it also chose to use an extra slot to feed the mainplane, in keeping with a solution it had used at the Singapore GP in 2009.

Mercedes introduced its first version of the F-duct at the Chinese GP, albeit in a very different guise to the other teams as it didn’t use the shark fin engine cover connected to the rear wing.

After testing its first version in Shanghai, Ferrari debuted its F-duct at Barcelona, but later removed it and found an update after the Turkish GP to be more effective.

The Scuderia also used supplementary inlets on the side of the airbox to feed the F-duct, as its airbox had already been optimised to feed the right amount of airflow to the engine.

Supplementary signal pipework was placed in the cockpit to allow the driver to use the back of his hand to activate the system.

Red Bull first tested its F-duct solution at the Turkish GP but was not entirely happy with the system. It made some alterations before it reappeared and was raced at Silverstone, with neutral pipework exiting above the main cooling outlet.

Force India introduced its F-duct at the ninth round of the championship in Valencia, where Williams also gave its own solution a debut. Its installation relied on a hole being created in the cockpit surround, with the signal pipework fed through the seat and cockpit padding.

Renault was another latecomer, only introducing its F-duct system – which also blew onto the mainplane – at the Belgian GP.